English II 2020

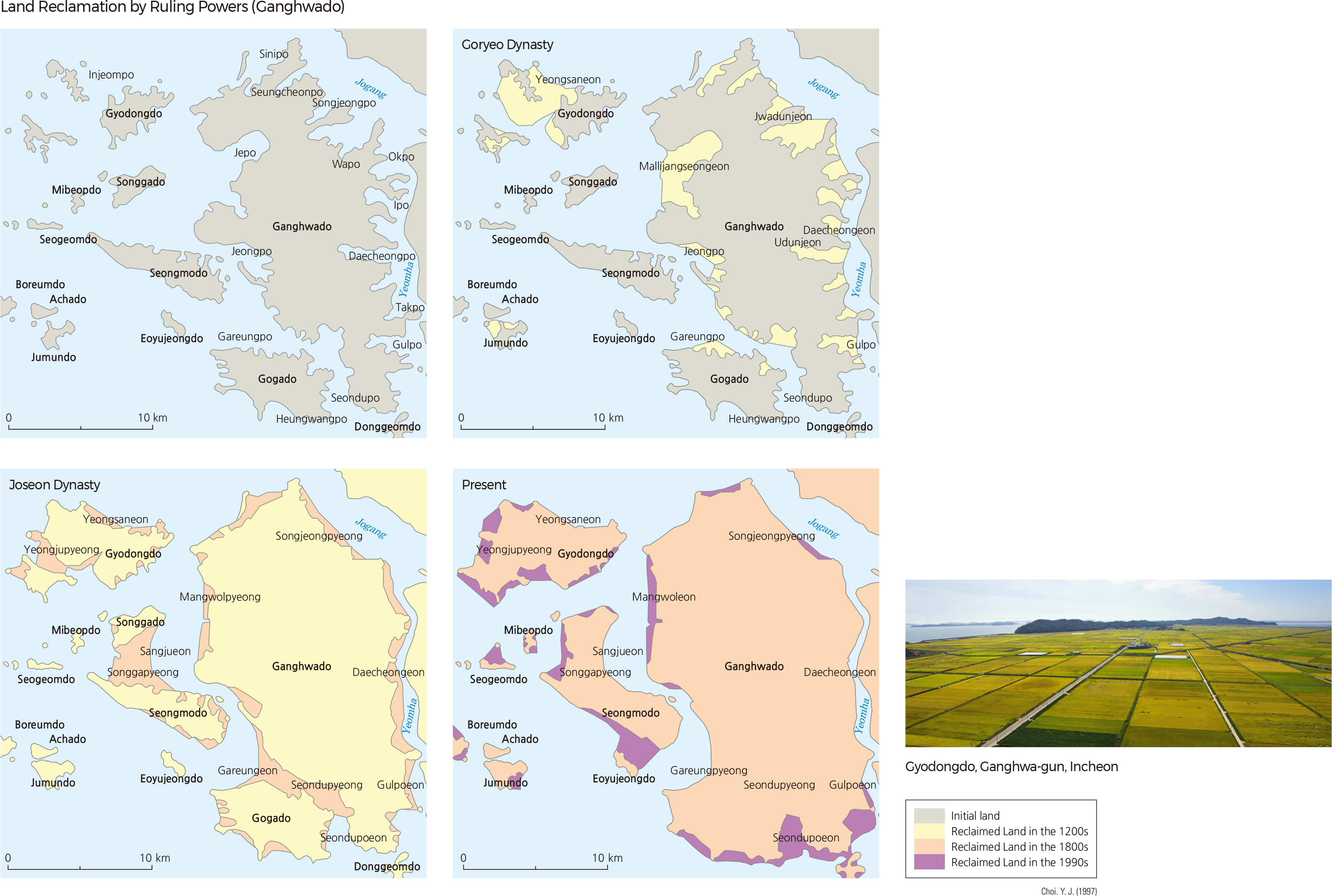

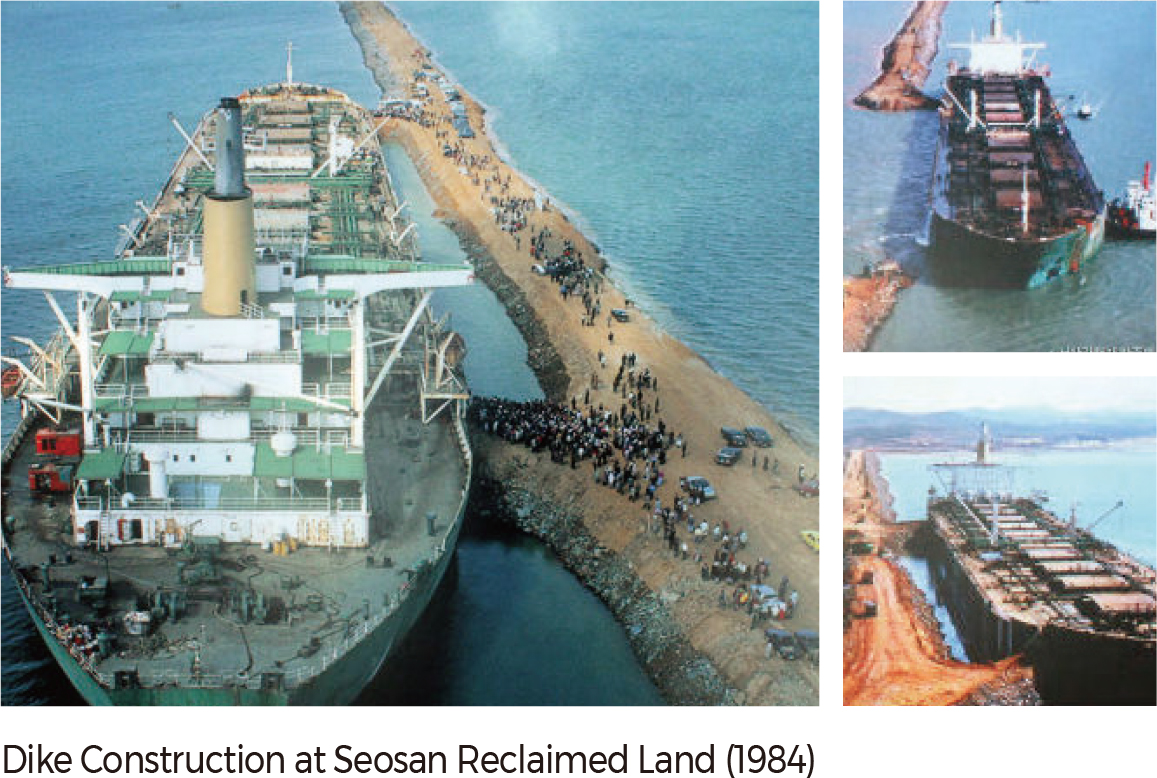

The southwest seashore, a deeply-indented coast with a shallow marine environment, is favorable for reclamation due to its extensive well-developed inner tidal flats. Land reclamation work has been undertaken throughout Korea’s history: for grain production and military provisions during the Goryeo and Joseon dynasties, and for rice production and land development during Japanese colonization. After liberation from Japanese rule, small scale land reclamation projects were carried out to enhance the food supply and abolish famine. Further projects were pursued for comprehensive agricultural development after the 1970s and for multi-purpose development after the 1990s.

Large-scale reclamation has destroyed the marine habitat; pollutants from the land have damaged the marine ecosystem and its diversity. Unlike other developed nations, Korea has not been making extensive shore restorations to repair affected regions. Central and local governments and organizations have carried out only some small-scale restorations since the 2000s. Restoring the coastal ecosystem is an essential task to maintain the ecological and social-economic capacity of the shores and promote further economic sustainability.

When the capital was transferred to Ganghwa in the 11th year of King Gojong of the Goryeo dynasty (A.D. 1232) due to the Mongolian invasion, the sudden surge in immigrants necessitated an enormous provision of food. As the war continued, the Royal Court planned a systematic reclamation project on coastal lowlands as its foremost agenda. In 1256, Jwadunjeon was reclaimed by building a dike in Jepo and Wapo, while Woodunjeon was reclaimed by blocking off Ipo and Choro of Yumha. During the period of King Gongmin, a new method of construction allowed for the blockage of deep tidal channels for wider land reclamation, as can be seen in the development of Yeongsaneon in the Injeompo area of Northern Gyodongdo.

Over the next 200 years (from the Joseon dynasty to the 1592 Japanese Invasion of Korea), no further large-scale reclamation projects were carried out. Afterward, Bipoeon, Bukjeokeon, Garieon, and Seondupoeon were built during the period of King Sukjong, with Seondupoeon being the largest reclamation project on Ganghwado. Reclamation on Ganghwado was completed in the late 18th century, and there was no longer any reclaimable land until the 1910s (except for the remaining salt ponds in southern Gulgotpo and Choji). Modern civil engineering technology in the 20th century has allowed for the resumption of reclamation work on some coasts, including the southern part of Ganghwado.

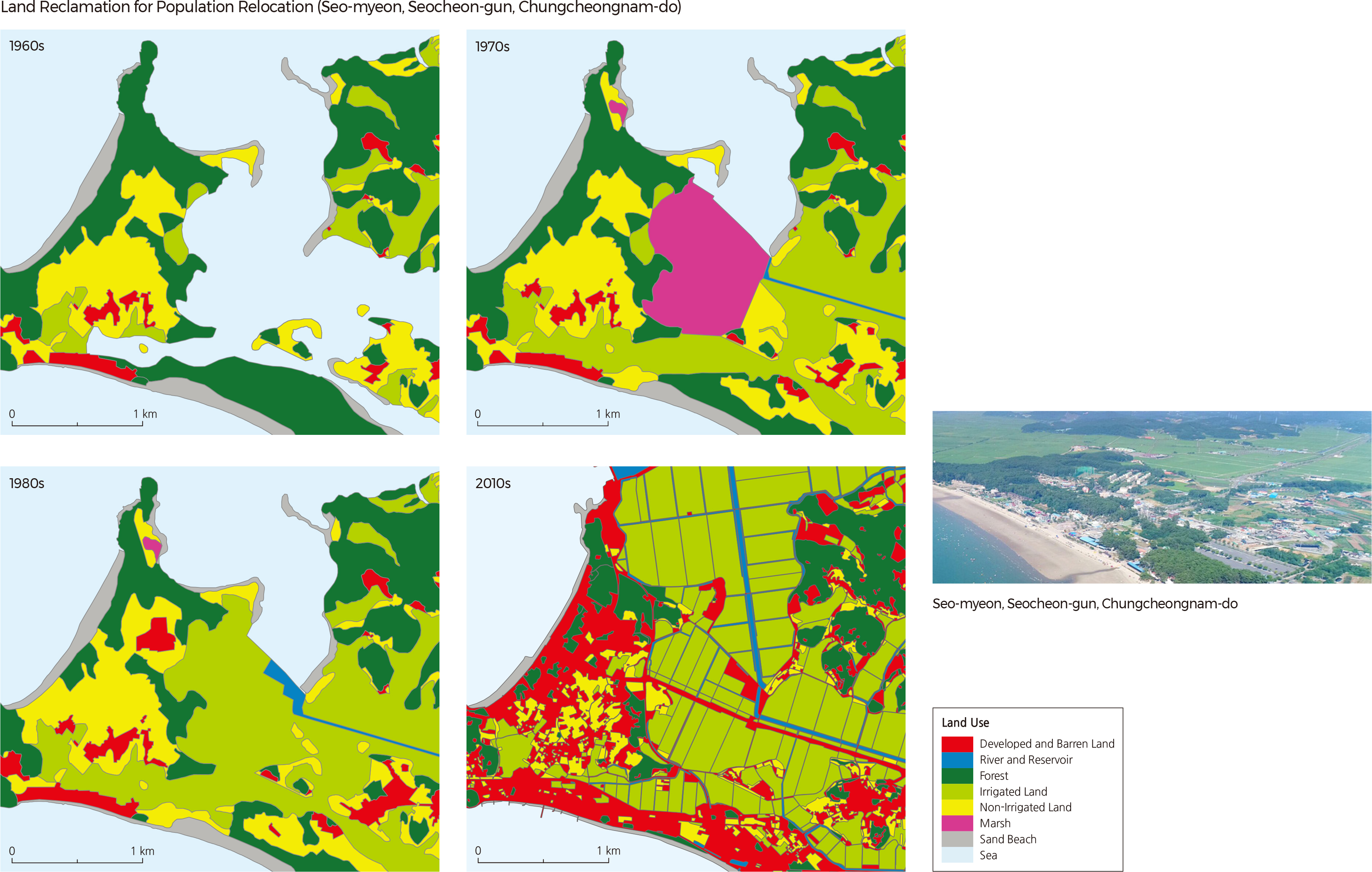

After the Korean War, a reclamation project was undertaken in the Dodun-ri area of Seo-myeon, Seocheon-gun, Chungcheongnam-do, which recruited war refugees as workers. Three to four households initially settled in 1954, followed by a steady rise of migrant settlement that resulted in approximately 100 households participating in the embankment project. Finished in 1961, the reclamation covered 614,876 ㎡ of public water and introduced farming just three years after completion. Construction costs were paid with a private loan under the condition of repayment after full completion, and other liabilities were fulfilled by selling land to residents in nearby regions. After reclamation was complete, the land was apportioned among the immigrants according to the number of days they participated in the reclamation. The last reclamation project (Busa district) was started by a private enterprise in the late 1980s and was completed in 1991. |