English II 2020

Baekdudaegan is a traditional system of geographical per-ceptions in Korea. From the past, Koreans have recognized the topographical features of the mountains that make up the Korean Peninsula as a connected stem system with a hierarchical structure.

The first literature in which the concept of Baekdudaegan appeared is Okryonggi, written by Doseon, a Goryeo monk in the early 10th century. He wrote, "Our country rises in Baekdusan and ends in Jirisan. It is the source of water and the land of tree trunks."

The first literature that used the term Daegan in Korea is Taekriji, written by Lee Junghwan in 1751. This book stated, "The Daegan was unbroken and stretched to the side, and went down thousands ri to the south to Taebaeksan in Gyeongsang-do to form a Maekryeong." The first literature that used the terms Baekdudaegan and Baekdujeonggan is Seongho saseo, written by Yi ik in 1760. He regarded Baekdusan as the starting mountain of Daegan and suggested a mountain range map using the term Baekdudaegan.

Shin Kyeongjun wrote Sangyeongpyo (circa 1770) to describe the Korean mountain ranges as a connected mountain system running from Baekdusan to Jirisan with hierarchical branches, which consist of one Jeonggan and 13 Jeongmaeks. He considered the mountain range and riverine system of Baekdudaegan as a fundamental base for understanding the people, philosophy, literature, ecology, and culture of the Korean Peninsula. When comparing Baekdudaegan and mountain range systems, the former organizes the mountains into hierarchically connected mountain trunks, while the latter organizes them into hierarchically connected tectolineament.

Sixty-four percent of South Korea is covered with forest, and most forests are connected to the Baekdudaegan. The Baekdudaegan, like the human backbone, has long been a central axis where interactions between humans and nature led to the formation of an eco-cultural space and spirit. Therefore, the designation of the Baekdudaegan as a protected area supports the identity of the Korean people and their willingness to maintain mutual dependency with the oceanic and continental ecosystems by strengthening the linkage between the cultures of the Pacific region and the Eurasian continent.

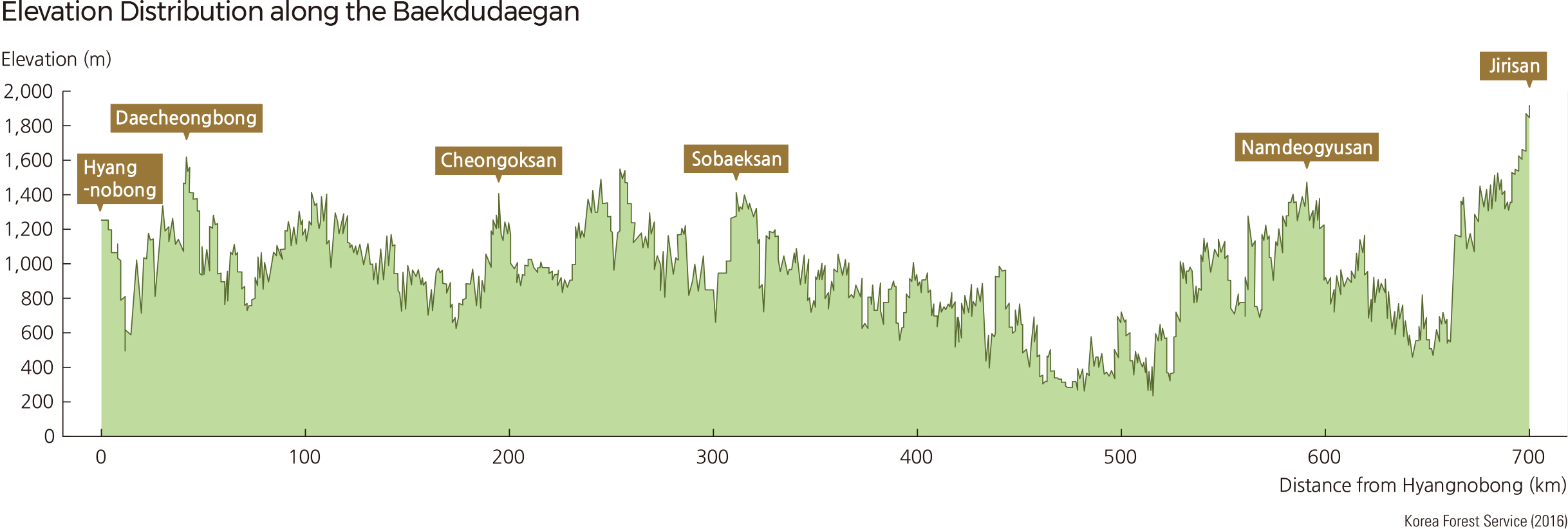

In September 2005, the Korean government designated the protection of an ecological corridor in the Baekdudaegan to preserve the natural environment of the Baekdudaegan and prevent damage from reckless development. The protected area was 864 km long from Hyangrobong in Goseong-gun, Gangwon-do to Cheonwangbong of Jirisan in Sancheong-gun, Gyeongsangnam-do, with an area of 263,000 ha, accounting for 2.6% of Korea. In November 2019, this protected area was expanded to 763 km in length and 275,465 ha in total area, accounting for 2.7% of Korea. The protected area consists of more than 500 mountains, peaks, and hills, including major Korean mountains such as Jirisan, Deogyusan, Songnisan, Sobaeksan, Taebaeksan, Odaesan, and Seoraksan.

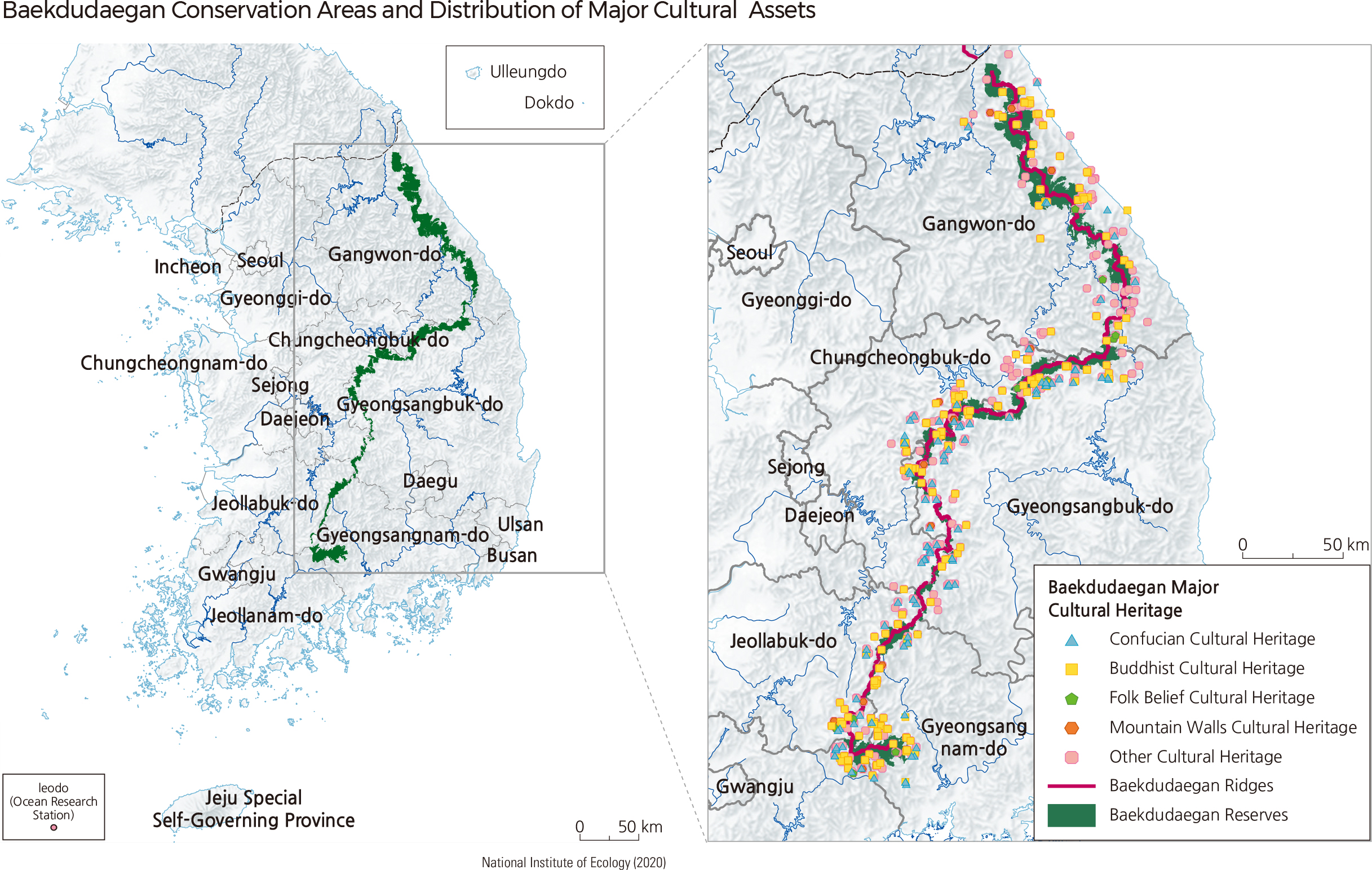

The Baekdudaegan protected area is extremely valuable in terms of Korea's cultural history. Each major mountain boasts temples that entwine Buddhist culture with impressive landscapes. The area houses elements of both tangible and intangible cultural heritage; there are 543 state-designated cultural assets, including 31 national treasures, 273 treasures, and 49 historic sites. There are also 965 province-designated heritage sites, 523 cultural and historical documents, 53 registered cultural heritage sites, and so forth. In particular, temple forests play a central role in enhancing the value of the protected area. Out of the 935 traditional temples in Korea, 173 (19%) are located in Baekdudaegan. Baekdamsa (Seoraksan), Woljeongsa and Sangwonsa (Odaesan), and Hwaeomsa (Jirisan) are the main temples well known to the public. They contain approximately 16,571 ha of temple forests, which accounts for 6% of the total protected area in Korea.

The Korea Forest Service developed four criteria for designating the Baekdudaegan Conservation Areas as follows: first, the Baekdudaegan conservation areas, as the core of the mountain range, should not be disconnected; second, the ecosystems of Baekdudaegan must be secured to ensure their continuity and connectedness; third, the boundaries of core and buffer areas must be defined by ecological factors such as riverine systems, mountain systems, and vegetation; and fourth, any negative impact to local residents must be minimized, and the opinions of diverse stakeholders must be considered. As of September 2005, based on these criteria, a total of 263,427 ha of the Baekdudaegan Conservation Areas had been designated. In terms of ownership, the conservation areas were composed of national forests (208,000 ha, 79%), public forests (20,000 ha, 8%), and private forests (35,000 ha, 13%).

An enforcement ordinance to protect the Baekdudaegan conservation areas was announced in November 2019. The designated area (275,465 ha) was divided into a core area (179,095ha) and a buffer area (96,369 ha). As a result, a sustainable management system was finally established to prevent damage to Baekdudaegan due to indiscriminate development. The Second Basic Plan for the Protection of the Baekdudaegan became a principle that considers sustainability, connectivity, comprehensiveness, and locality. It is also a necessary standard to promote the conservation and wise use of the environment. Furthermore, international cooperation between various countries is being promoted, such as enacting joint management of the Baekdudaegan between the two Koreas, designating the Baekdudaegan as an international protected area by international organizations such as the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN), and participating in the establishment of an ecological network in Northeast Asia.

Diverse wildlife lives in the Baekdudaegan region, although the Baekdudaegan contains only 4.3% of the total forests of Korea. Studies indicate that Korea's flora consists of 126 families, 541 genus, and 1,248 species (3 subspecies, 204 varieties, 22 forms). Its fauna includes 23 species of mammals (such as otters, martens, leopards, and flying squirrels), 91 species of birds (including 12 legally protected birds), 11 amphibians, and 6 reptiles.

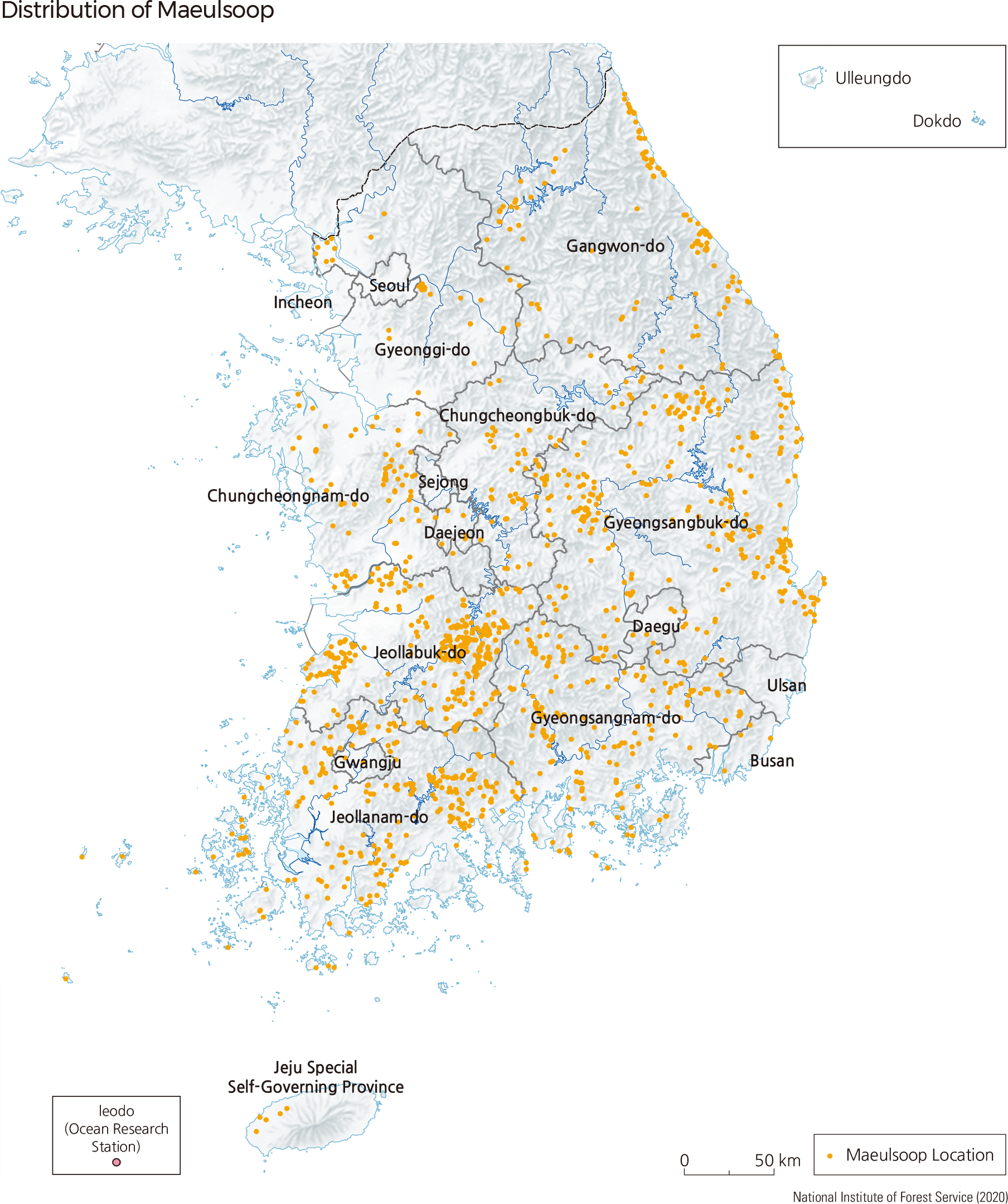

Korean traditional villages took the concept of the Baesanimsu (with back to the mountain and face to the water) as the basic principle to guide settlement location and land use. Also, this principle greatly benefited villagers who, as a result, lived within well-secured watersheds with access to water, protection against the wind, and accessibility to resources. The traditional villages were adapted to the local natural conditions. They existed in a harmonious relationship with the surrounding natural ecosystems, resulting in their ability to maintain that spatial arrangement for a long time. One good example is maeulsoop (village grove).

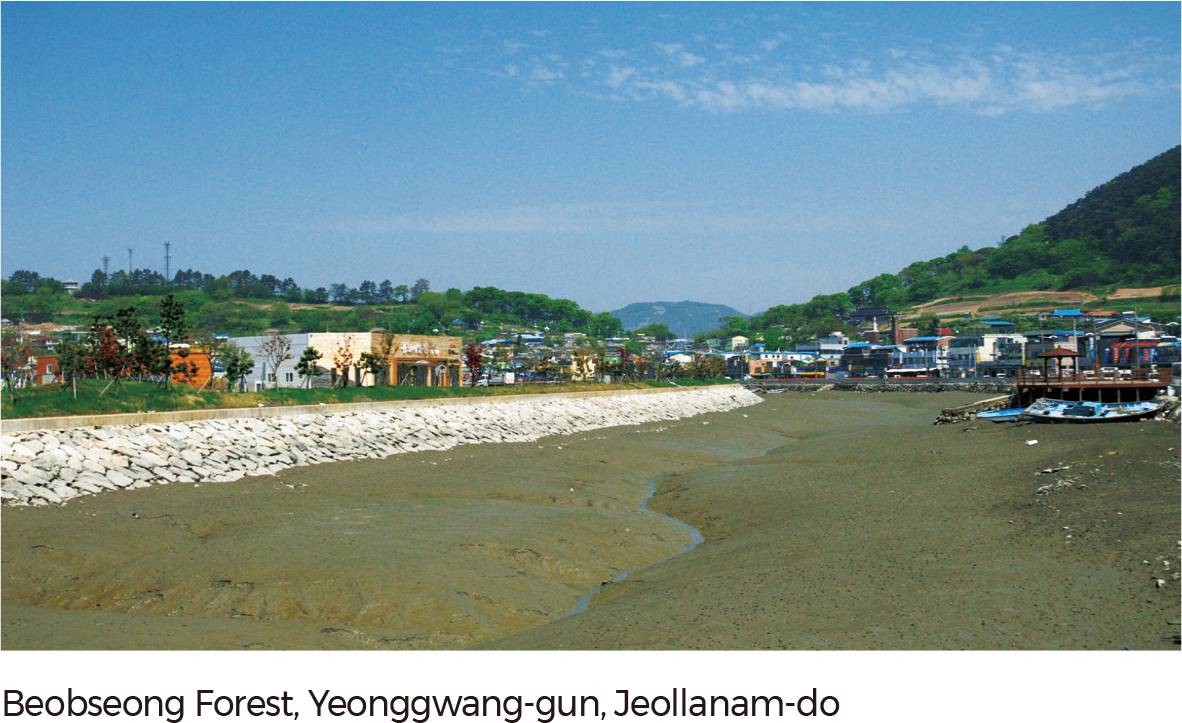

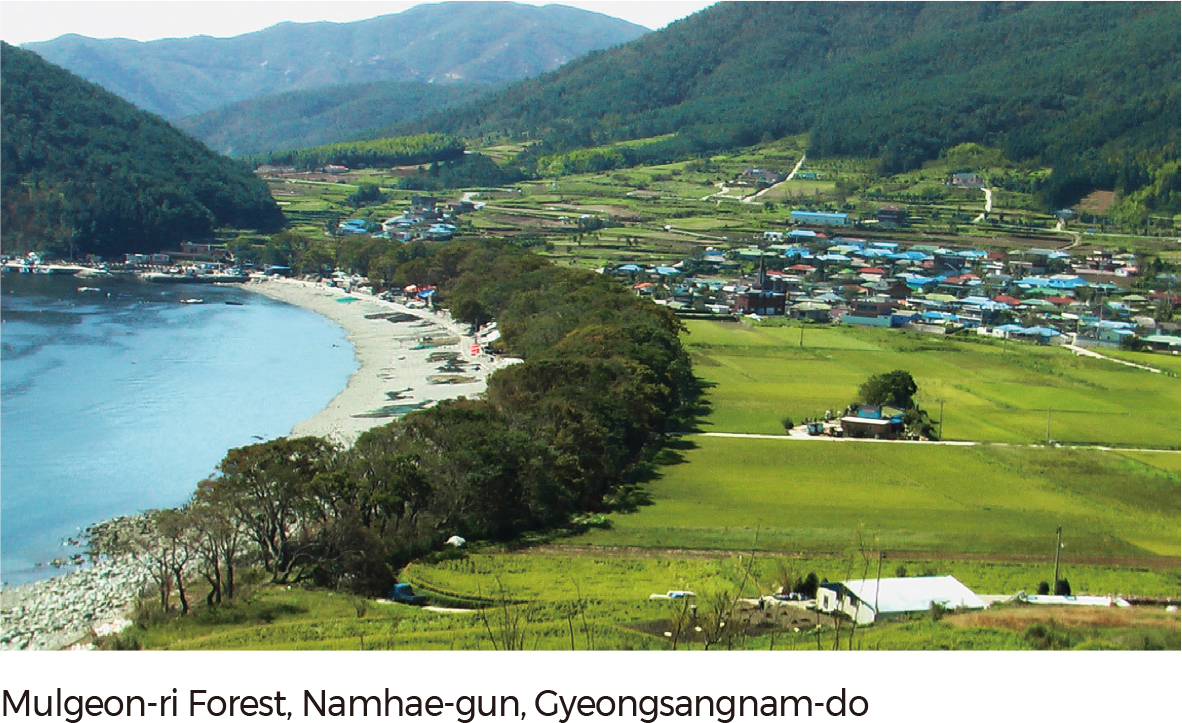

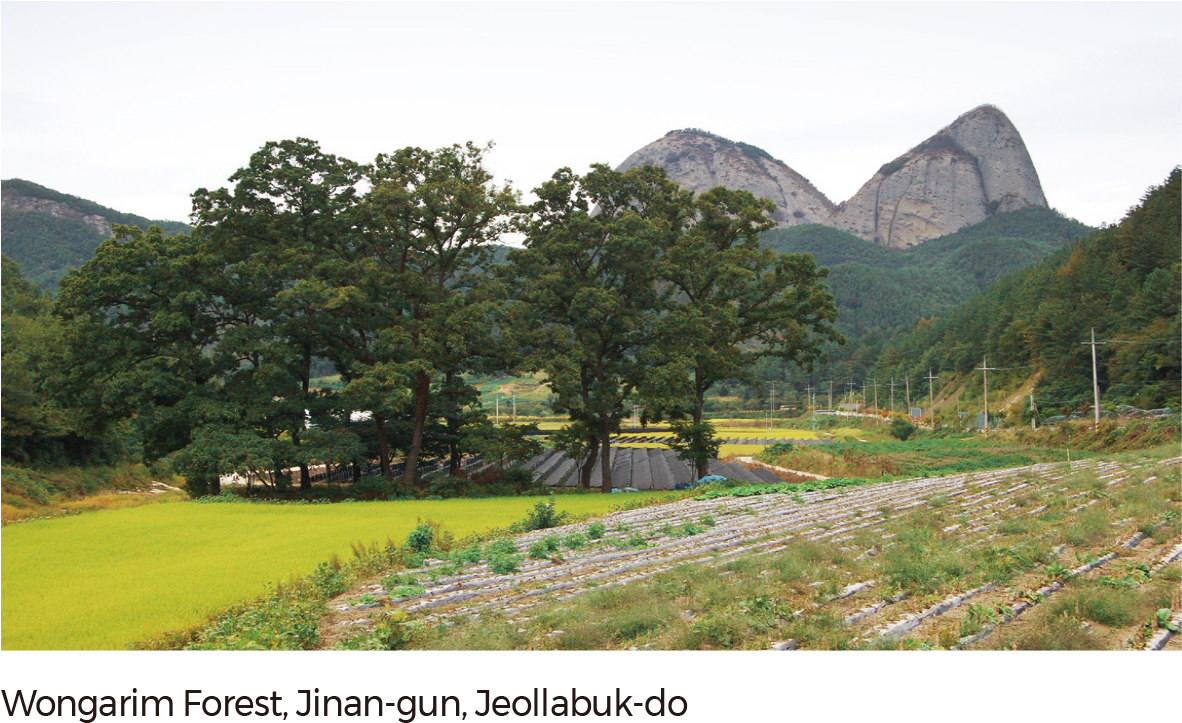

A village grove is a forested area that helps the people adapt to the monsoon climate and helps the village to harmonize with the surrounding environment. The grove is a part of the village landscape or a property co-owned with villages and protected and managed by villagers.

A village grove is a common gathering place for villagers and provides shelter for people during the hot summer. Furthermore, it is a sacred site and holy place that the villagers protect. Ancestral rites are held periodically in a village grove.

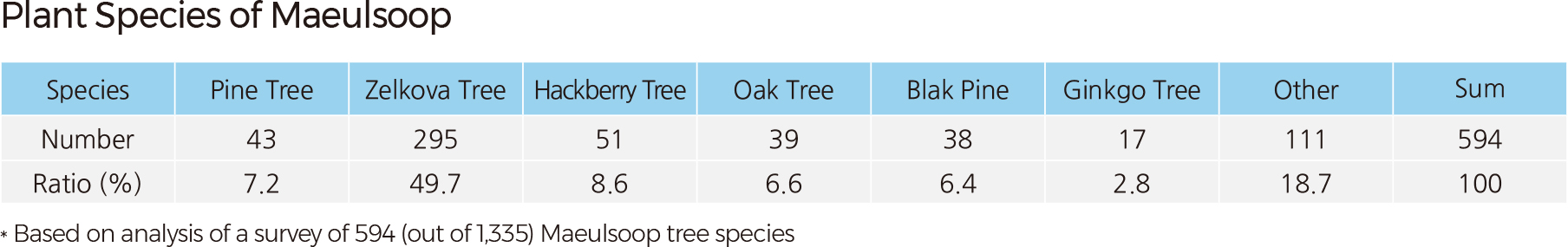

Big trees such as pine and zelkova grow in the groves. Also, many bird species like Mandarin Duck, Scops Owl, Owl, Woodpecker, Great Tit, and Starling, which normally live deep in the mountain forests and build nests in the hollows of tree trunks and branches, inhabit the area, frequently being observed near the village.

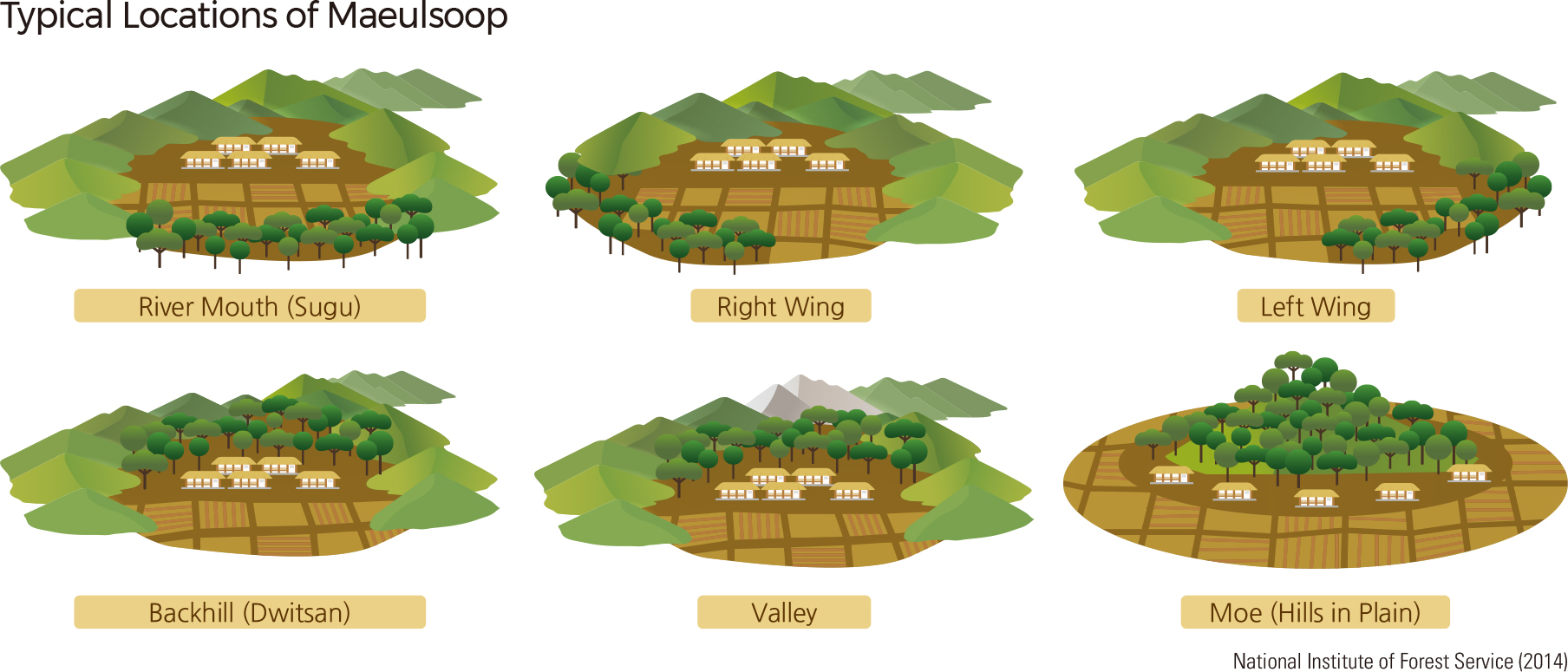

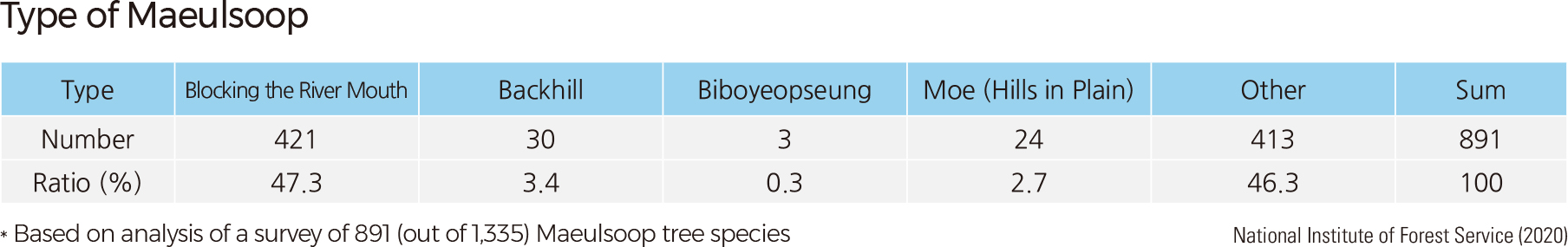

Based on their location, village groves can be classified into the following five types: sugu (a grove covering the mouth of a watershed in which the village is nested), yeop (a grove covering low areas either on the left or right side of the village), dwitsan (a grove covering the ridge of low hills behind the village), gyegok (a grove covering an unsightly object in the valley behind the village), and meoi (a grove covering an isolated hill).

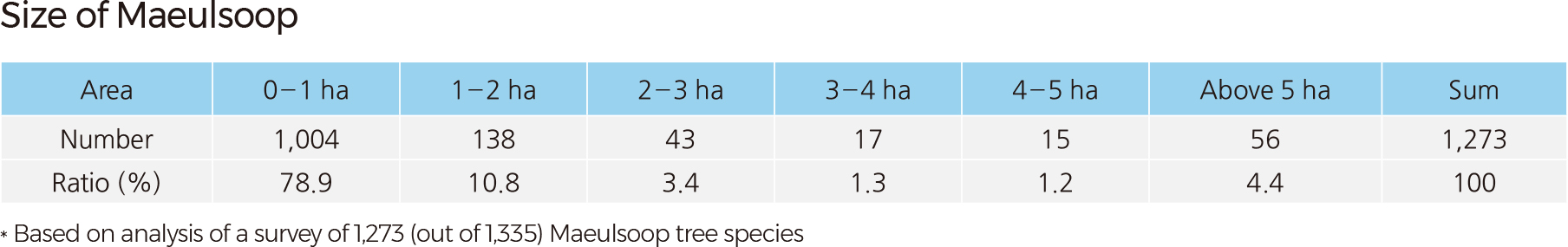

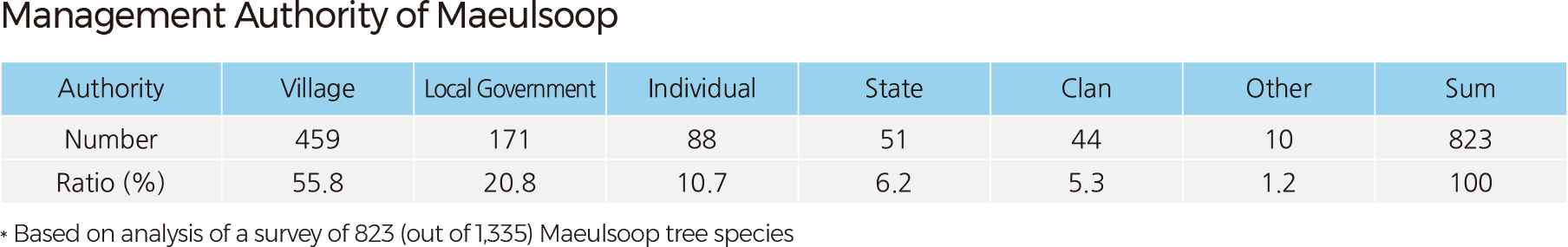

The Korea Forest Service had investigated and organized information for the village groves in 1,335 regions as of March 2020. Most of the village groves are small. Forests with less than 1 ha account for about 78.7% of the total village groves. Major plant species of the village groves on the list are Pinus densiflora and Zelkova serrata. Sugumagi, a type of grove for slowing the flow of water, was the most common type of village grove.

The oldest village grove in Korea is Daegwallim, which is thought to have been created with levees by Choi Chiwon to prevent floods during his term of office as governor of Cheollyeong-gun during the reign of Queen Jinseong (A.D. 887– 897). The grove is protected as Natural Monument No. 154. In the grove, various plants are found such as Sawtooth Oak(Quercus acutissima), Oriental Cork Oak (Quercus variabilis), Asian Hornbeam (Carpinus tschonoskii), Abundant-flower Meliosma (Meliosma myriantha), Tallow Tree (Sapium japonicum), Sawleaf Zelkova (Zelkova serrata), and East Asian Hackberry (Celtis sinensis).

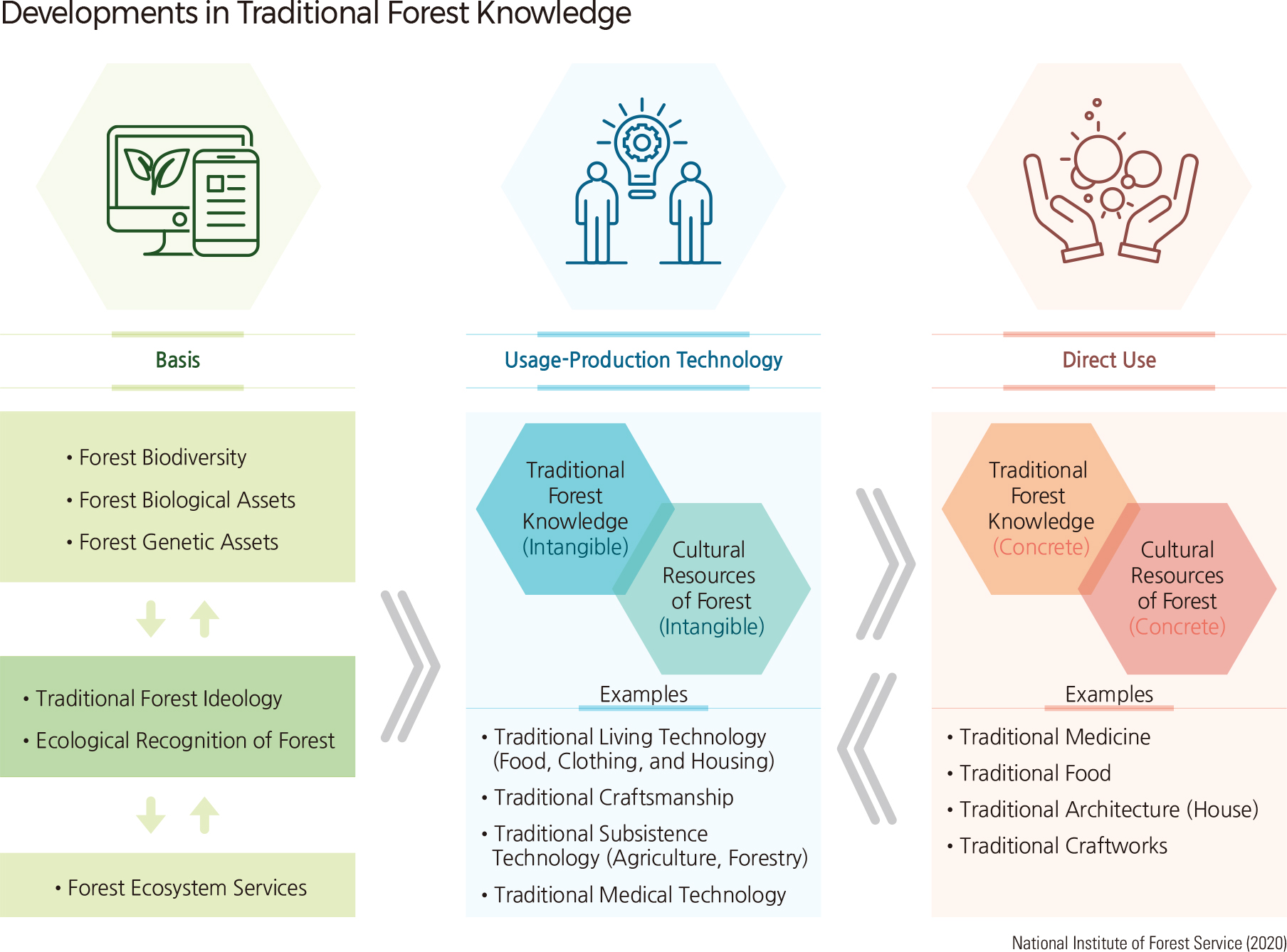

Traditional forest knowledge is an integral aspect of the cultural heritage, ecological (genetic) resources, and traditional wisdom that a particular region or a group of people (tribe or ethnic group) has passed down over the generations. Based on this, Korea has developed usage, production, and related technology for traditional knowledge. Recently, efforts have been made to establish a classification system for traditional forest knowledge types to fit the international trend toward the traditional knowledge-related International Patent Classification (IPC). This system classifies traditional forest knowledge into five categories (humanities, forest philosophy, natural environment, production technique, and social-economic policy) and also classifies the knowledge into 33 tangible resources and 31 intangible resources. Tangible resources include traditional village groves, mountain fortresses, beacon mounds, and markers of the forbidden forests. Intangible resources are traditional lifestyles that are being forgotten, such as Songgye and Hyang'yak.

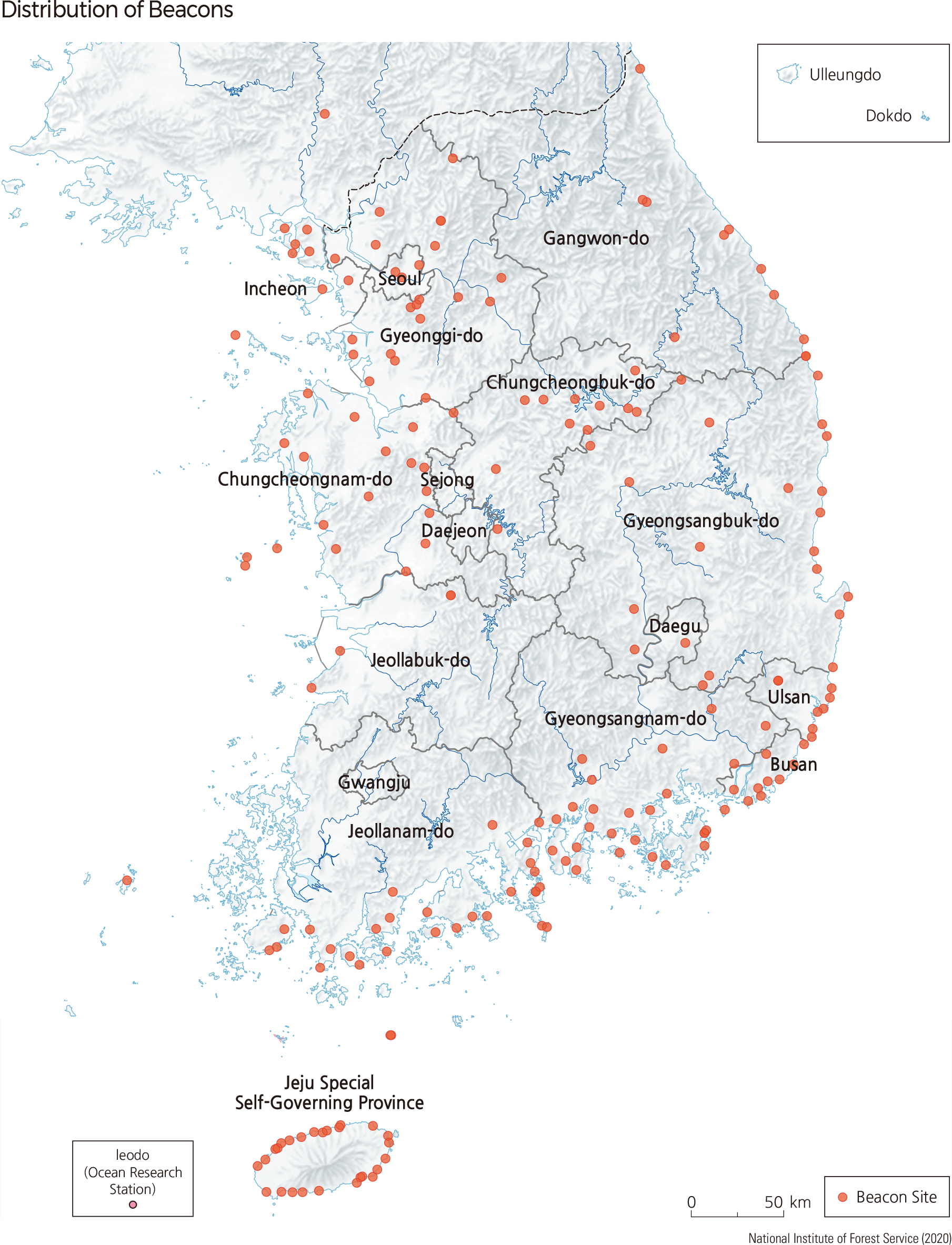

Beacon mounds, which signaled urgent matters via smoke and fire, are a representative example of tangible resources and an important communication tool used in traditional Korean society. In particular, beacon mounds on mountains and travel beacons were used as an effective means of communication. Currently, the locations of 194 beacon mounds have been identified.

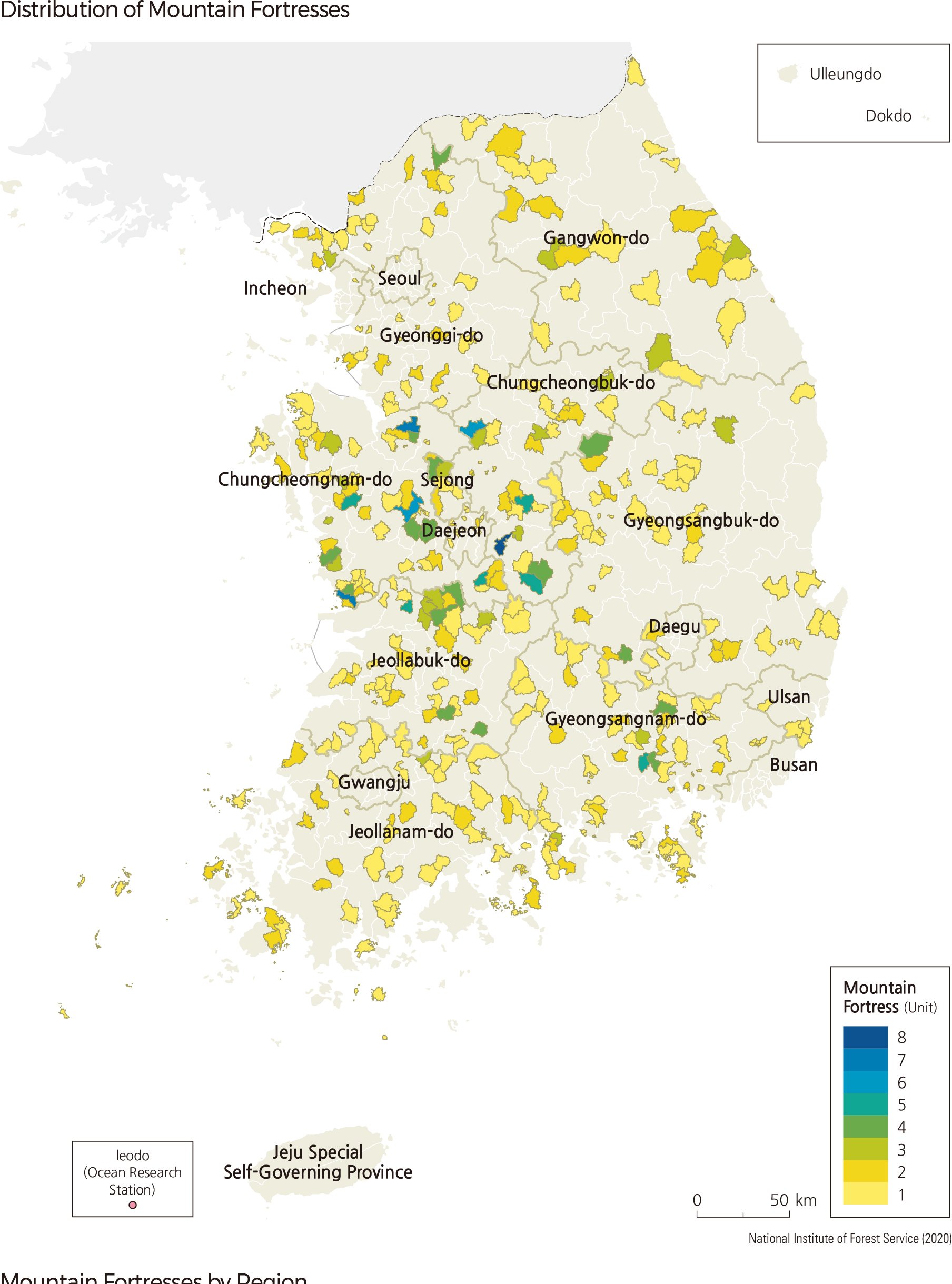

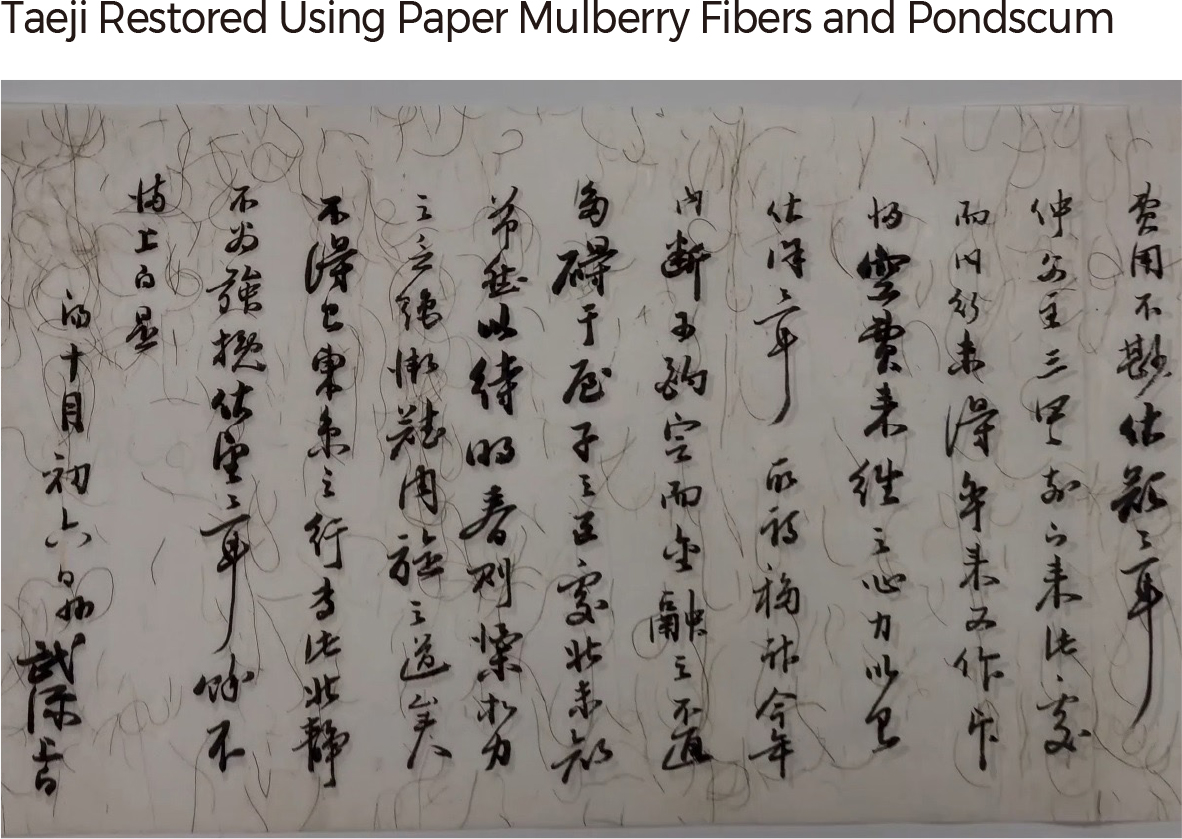

Mountain fortresses use trees, soil, and rocks to prevent enemy attacks in accordance with the terrain. As a tangible resource, a mountain fortress includes the structures created and the forest resources within it. As of 2020, a total of 1,331 mountain fortresses are identified. Recently, mountain fortresses and beacon mounds have become important as urban observation sites and ecological landscape resources. The core raw material of Taeji, a traditional Korean paper, was pondscum (Spirogyra spp.). In 2020, the National Institute of Forest Sciences restored Taeji using mulberry paper fibers and pondscum. The method of making Taeji was not known, but it was restored through the investigation of old literature and microscopic analysis.

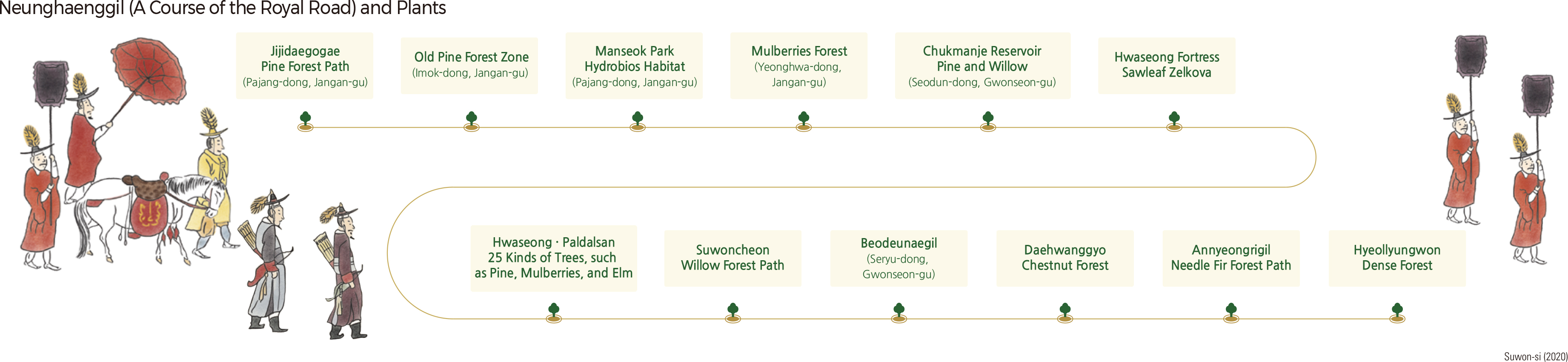

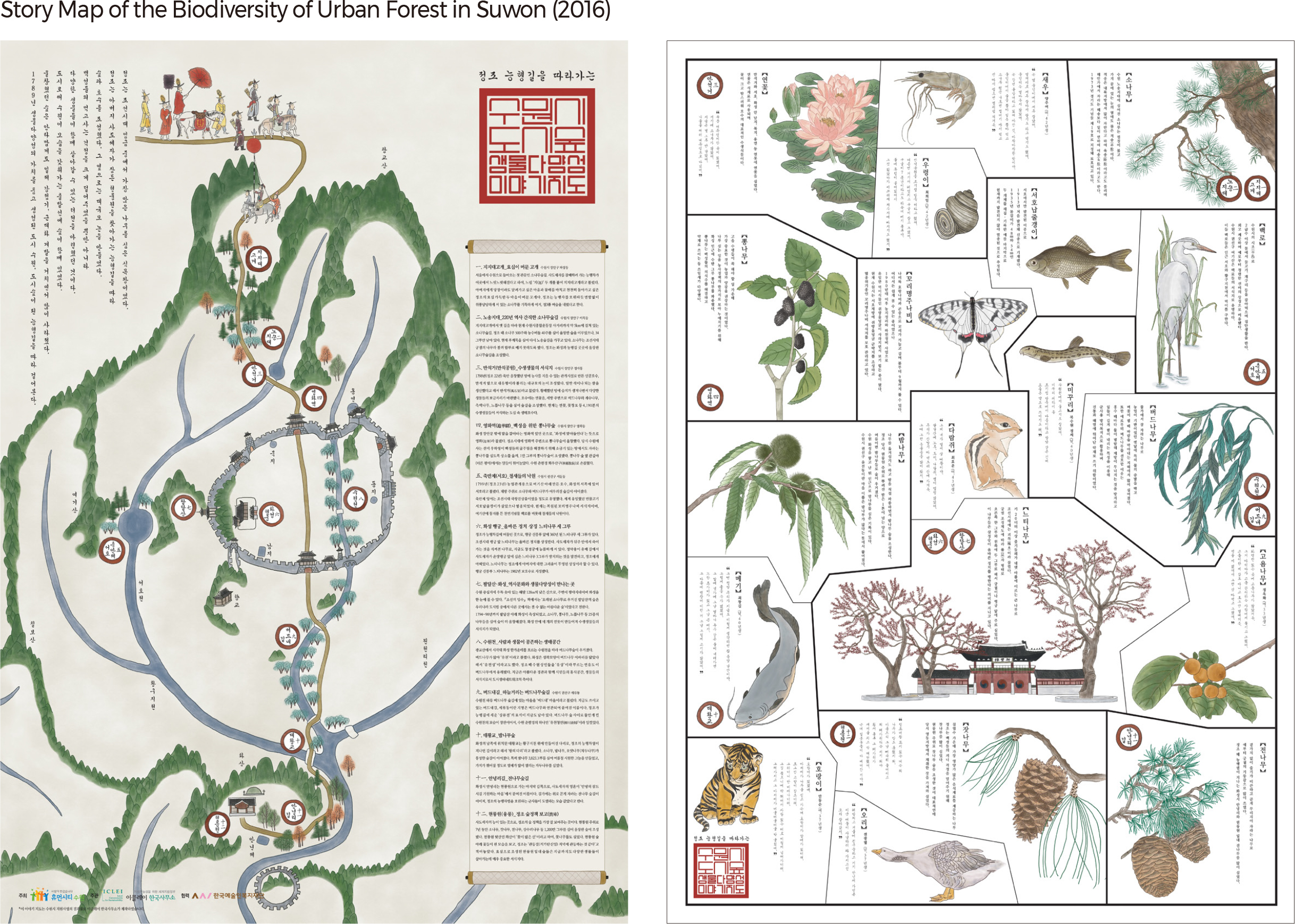

Biodiversity is a component of local history and culture and a key resource that can be linked to cultural services provided by ecosystems. Suwon was a planned city built by King Jeongjo. Suwon has historical and cultural resources related to biodiversity. In Suwon, urban forests have been built around the Hwaseong Fortress, which was designated as a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 1997, and Neunghaenggil (a course of the royal road). King Jeongjo planted the most trees of all the kings in the Joseon dynasty. He constructed the Hwaseong Fortress in 1794-1796 and visited Hyeonryeongwon, where his father, Prince Sado, was buried. Along this royal road, forests were created, and wetlands such as reservoirs and large rice fields were built as irrigation facilities. Even today, Suwon has several place names derived from trees planted during the King Jeongjo period.

The International Council For Local Environmental Initiatives (ICLEI) is an international non-governmental organization that promotes sustainable development. Suwon has signed the Durban Commitment for Biodiversity. In 2016, Suwon collaborated with the ICLEI's Korean office to create a story map of the biodiversity of urban forests in Suwon as part of Local Action Biodiversity (LAB). The story map along the Neunghaenggil consists of pictures and easy explanations of various species and their main locations in Suwon's history. This map can be used as an explanatory book on history and culture or educational material for experiencing biodiversity. |