English II 2020

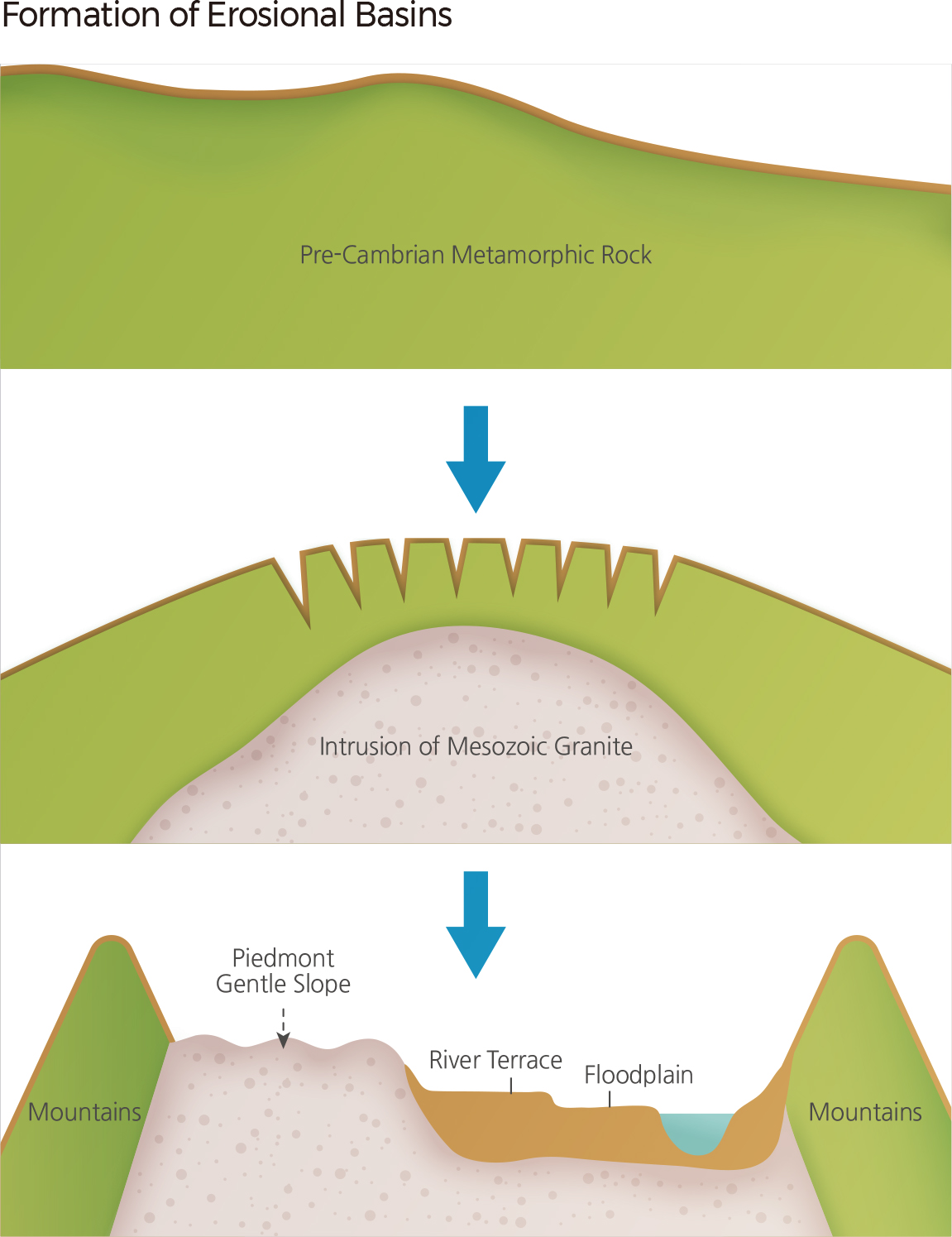

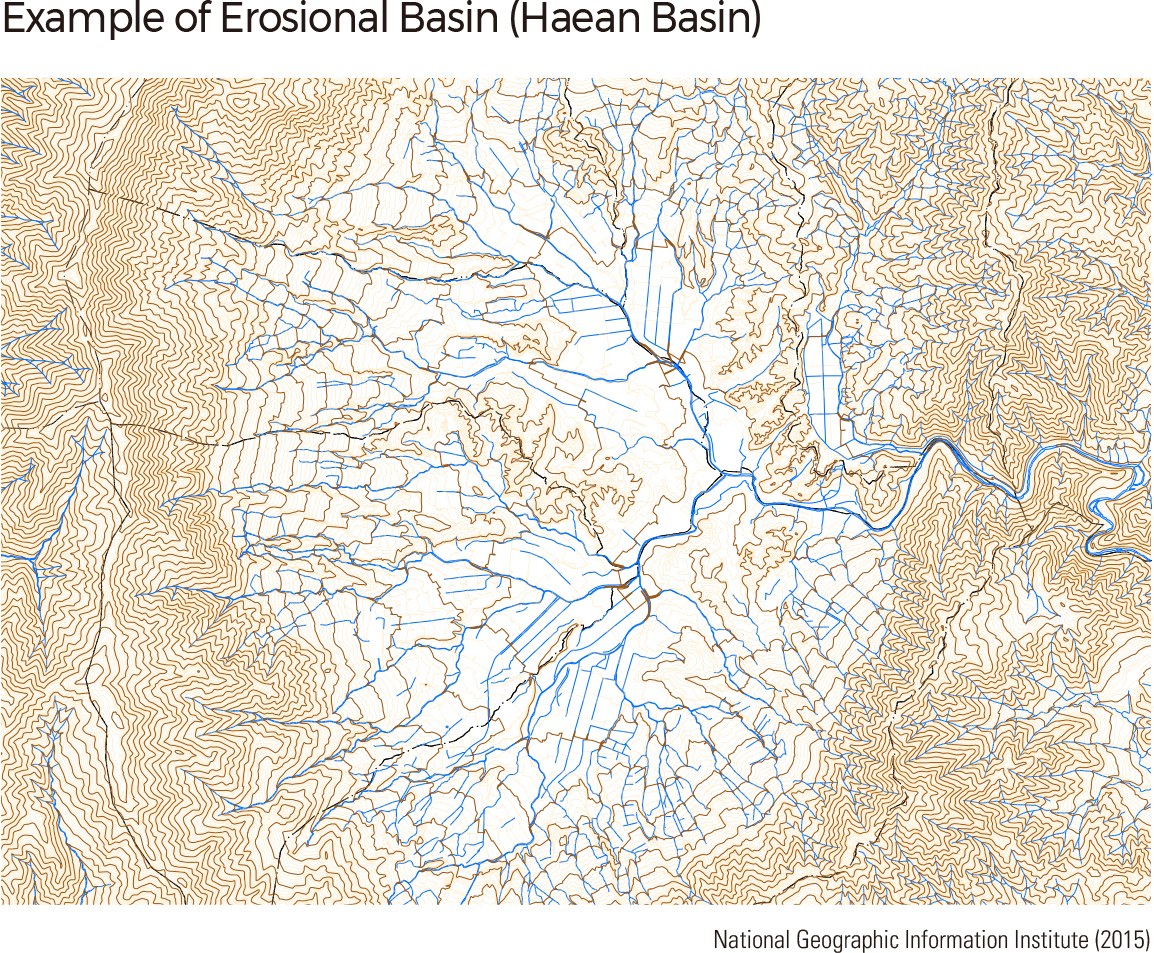

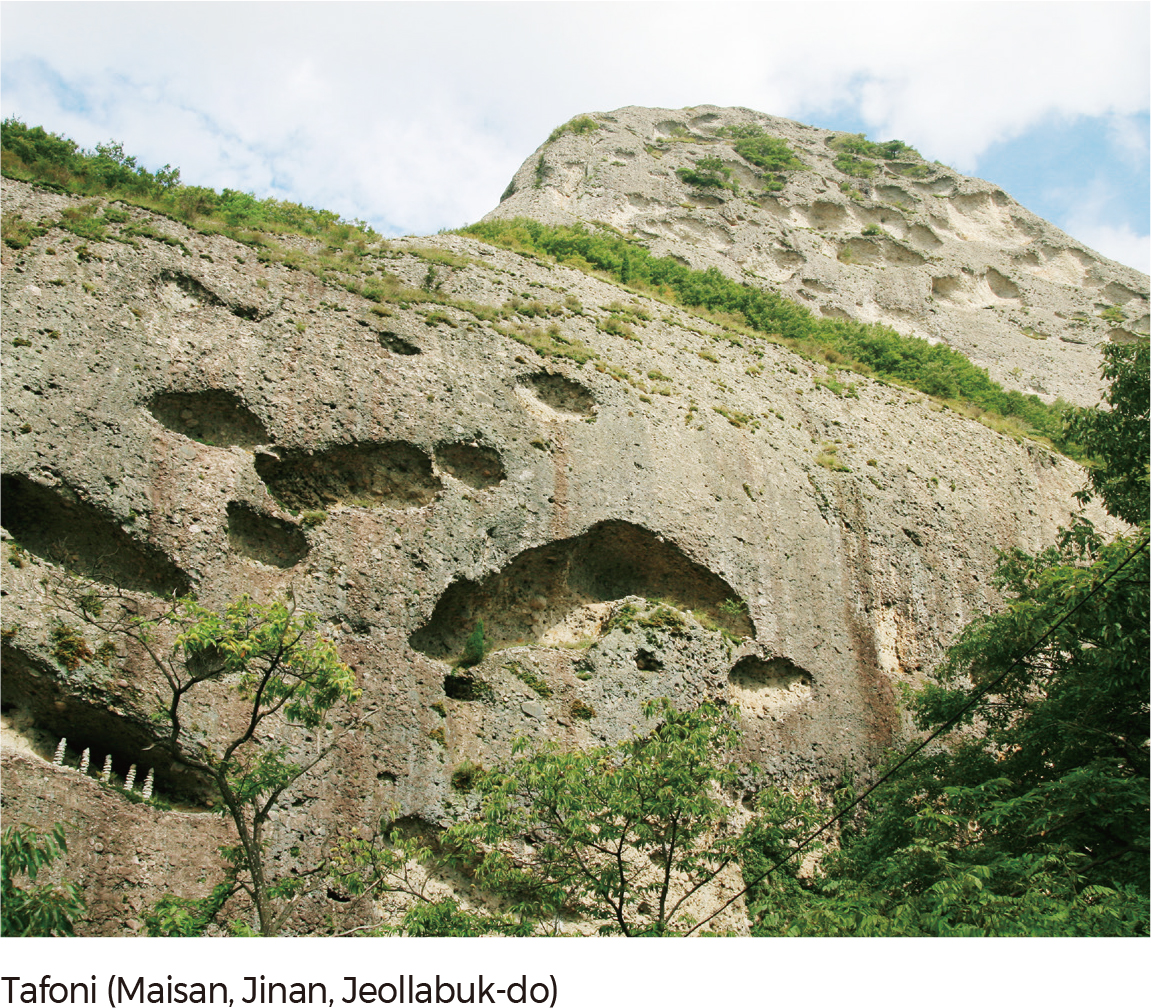

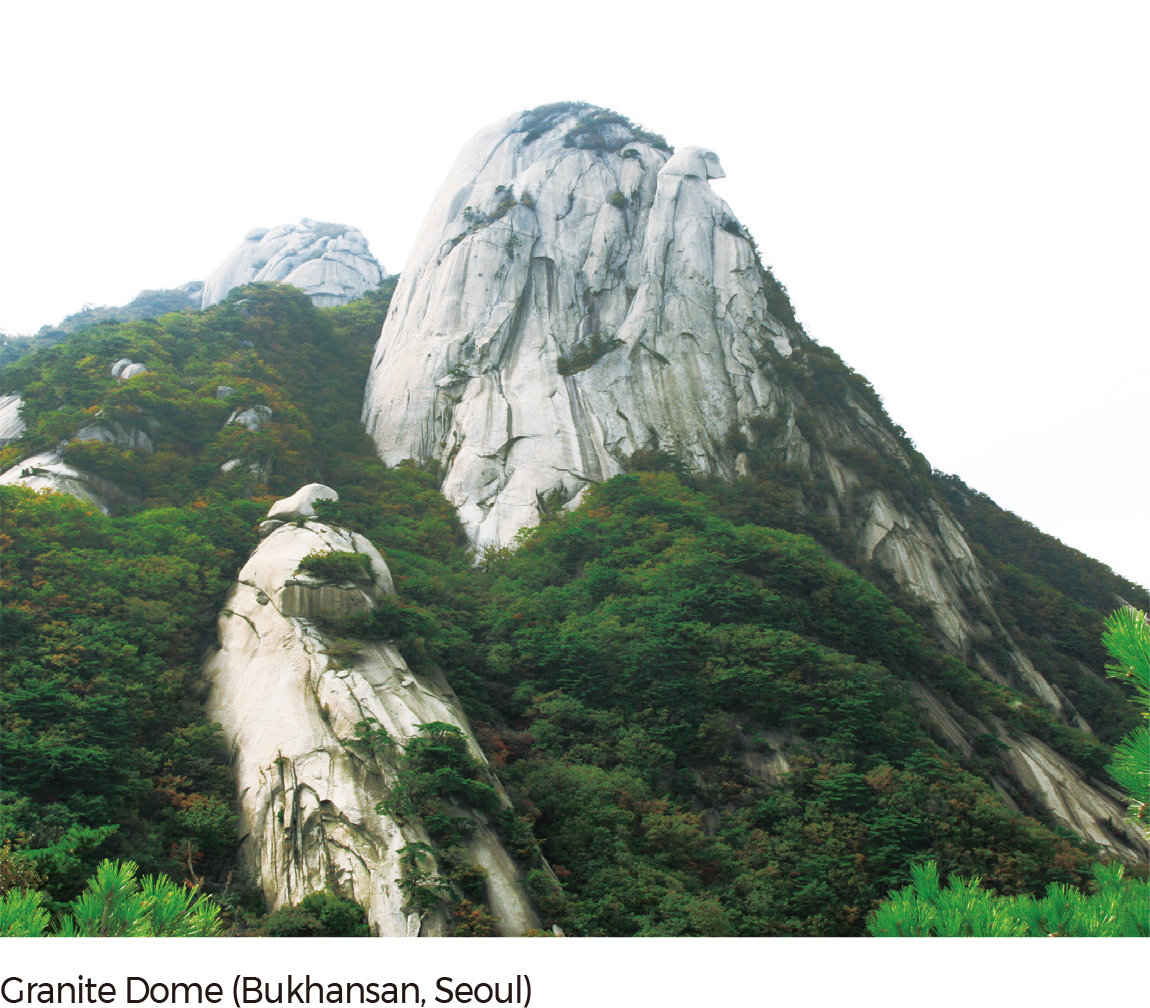

Although approximately 70% of Korea's territory consists of mountainous areas, there are not many mountains with high elevations. The highest peak in South Korea (excluding Hallasan in Jejudo) is Jirisan, which stands less than 2,000 m. The higher mountains are distributed toward the eastern side, a phenomenon that can be explained by the asymmetrical warping of the Korean Peninsula. Bedrock that is resistant to weathering and erosion constitutes the high rugged mountains, while less resistant rocks characterize the lowlands, basins, and valleys. South Korea displays a complex topographic regime due to various bedrock compositions formed over different geological periods. For example, metamorphic rocks originate from the Pre-Cambrian, granite and volcanic rocks were formed during the Mesozoic, and sediments remain from the Tertiary and Quaternary. Typical eroded and weathered landforms include erosional basins, sinuous rivers, rock cliffs, rock domes, tors, tafoni, and caves, while depositional landforms include block streams, talus deposits, and upland wetlands. According to the Natural Ecosystem Survey, firstgrade landforms are generally located along the high mountains of Taebaeksanmaek and Sobaeksanmaek and are also widely distributed in island areas.

Rivers in Korea can be classified as straight, meandering, or braided. Straight rivers are bounded by exposed bedrock between narrow valleys and mounds, and meandering rivers develop on wide floodplains. Typical erosional landforms include waterfalls, potholes, riverine cliffs, and riverine caves, while typical depositional landforms include deltas, alluvial fans, riverbanks, point bars, and riverine wetlands. The floodplains formed by Hangang, Nakdonggang, and Geumgang constitute major agricultural plains in South Korea. The natural levees and backswamps of these floodplains developed from the last glacial period; eroded valleys were filled with sediments due to rising sea levels. Deltas, which are an extension of floodplains, are shaped by sediment discharge of rivers, ocean tides, and waves. They are generally located where the mouth of a river on the floodplain meets the sea. Nakdonggang Delta is a representative example. Alluvial fans are formed from small rivers and are mainly used for agriculture. Most eroded stream topography is observed in upstream areas of large rivers or around smaller rivers. In Korea, many of these regions have become tourist destinations as the exposure of bedrock creates a unique landscape. As a result, the most notable examples of river topography within the nation are generally located in upstream regions, rather than near the mouth of a river.

Korean coastal landforms can be classified as rocky, sandy, or muddy. Sandy coasts are observed in bays where active sedimentation by waves occurs. Coastal depositional landforms include beaches, sand dunes, sand spits, sand bars, lagoons, and tombolo. Sandy coasts prevail in the eastern and western coastal areas, especially along regions exposed to the open sea, such as the Taean Peninsula. Rocky coasts are indicative of erosional topography and develop along the headlands of mountainous and mound regions near the sea or where wave activity is strong. They are often found near major mountain ranges along the eastern and southern coasts. Sea cliffs, wave-cut platforms, and coastal terraces are also visible along the eastern coast of Korea. Muddy coasts are found along the western and southern coasts where flood and ebb tides are farther apart, wave activity is weak, and silt-sized particles are deposited. The largest tidal flats occur in Gyeonggiman (Gyeonggi Bay), where the tidal range is as large as 8–10 m. First-grade coastal landforms are evenly distributed along the coastline, mainly around relatively less-developed islands.

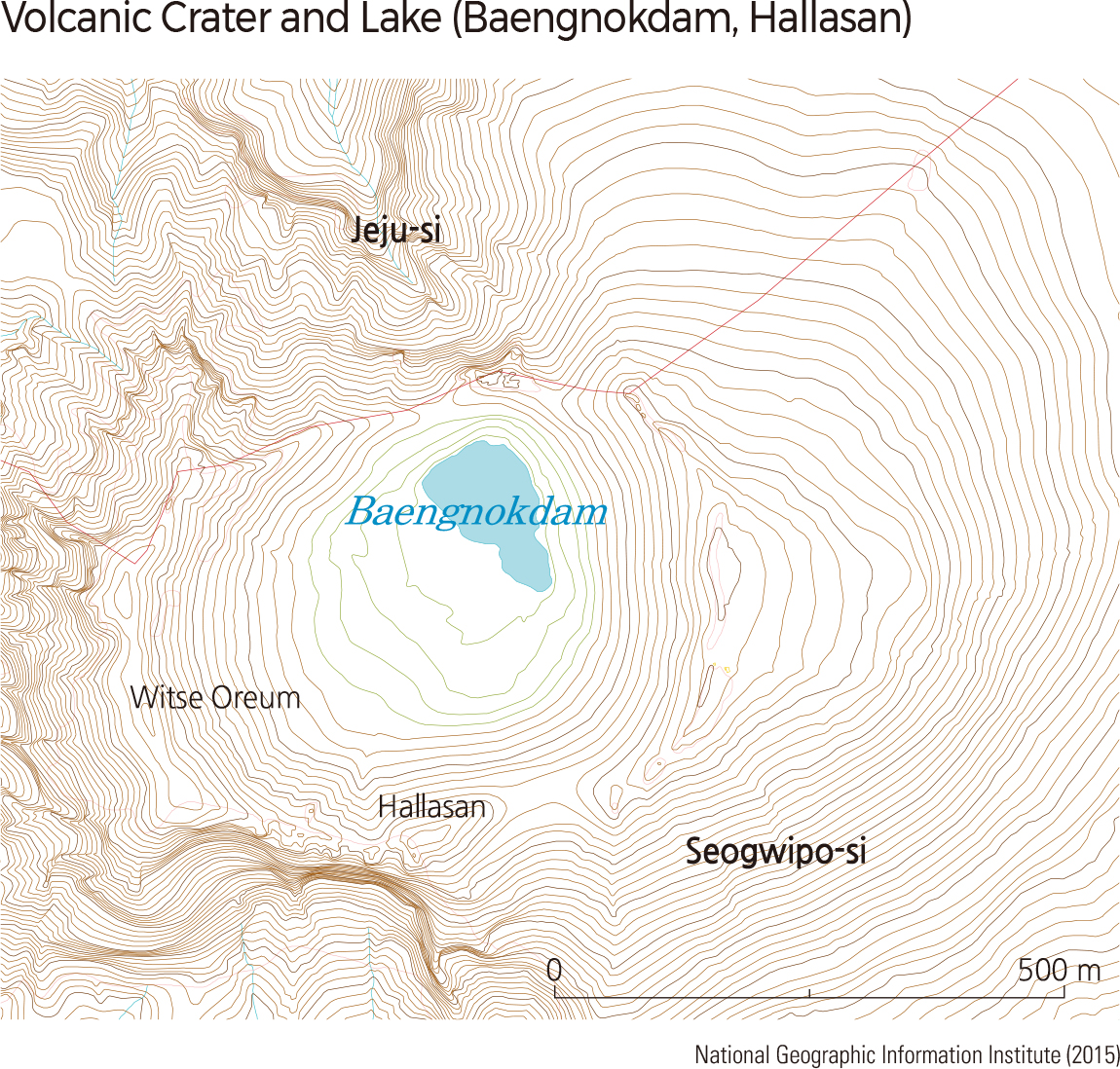

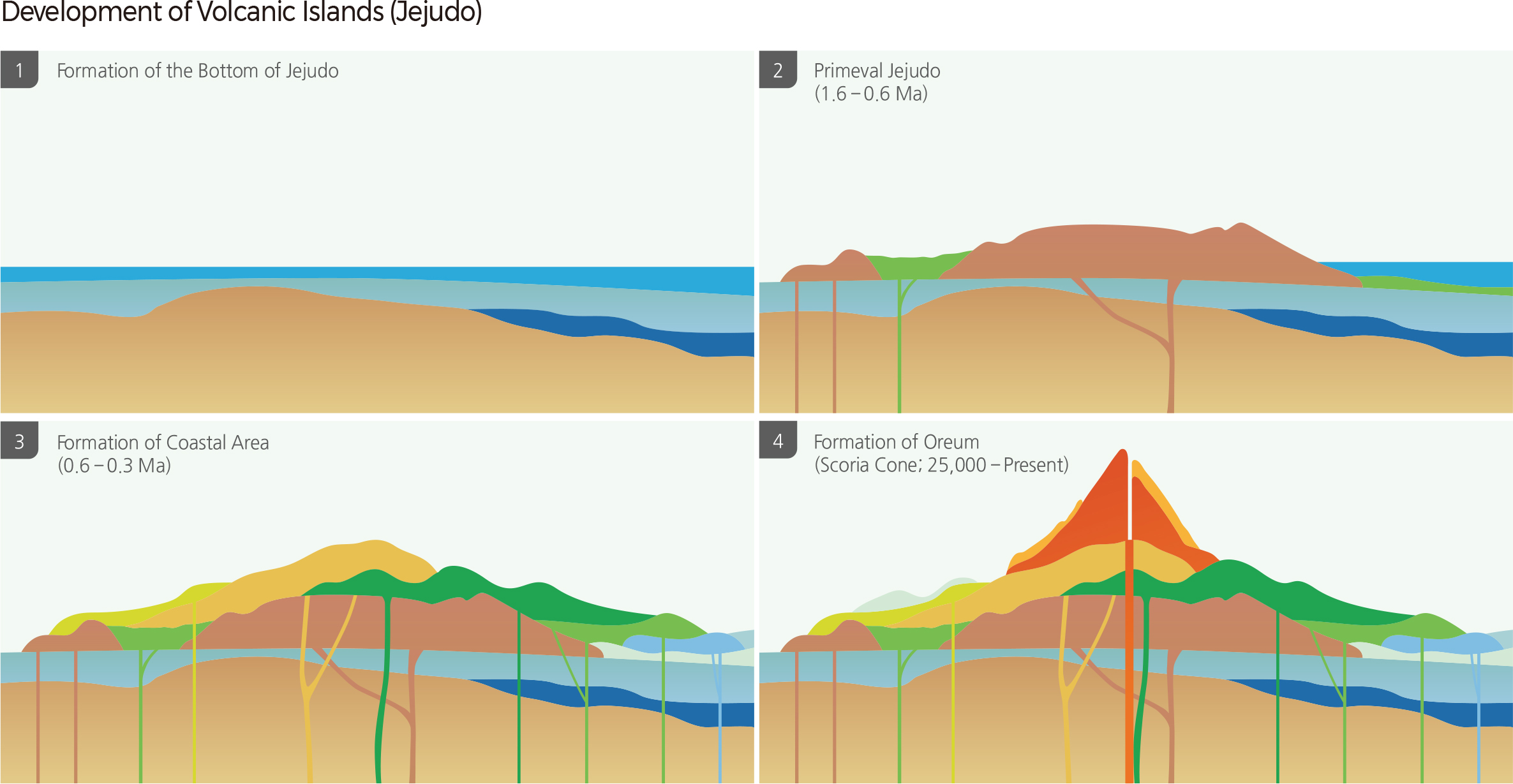

Although Korea does not currently have active volcanoes, vigorous volcanic activity occurred throughout the Quarternary period. As a result, distinct volcanic landforms can be observed in Jejudo, Baekdusan, Ulleungdo, Dokdo, and the Cheorwon Plateau. Jejudo, home to Hallasan, measures 73 km from east to west and 31 km from north to south with an area of 1,847 ㎢. It is an ellipsoid shape extending E-NE and has gentle slopes, which is typical for a shield volcano. Jejudo was formed by hydro-volcanic activity during the Quaternary and displayed diverse volcanic landforms that are not generally seen on the Korean Peninsula. It has recently been designated as a geopark and a UNESCO World Heritage Site. This can be seen as an acknowledgment of Jejudo’s landscape value as a natural resource.

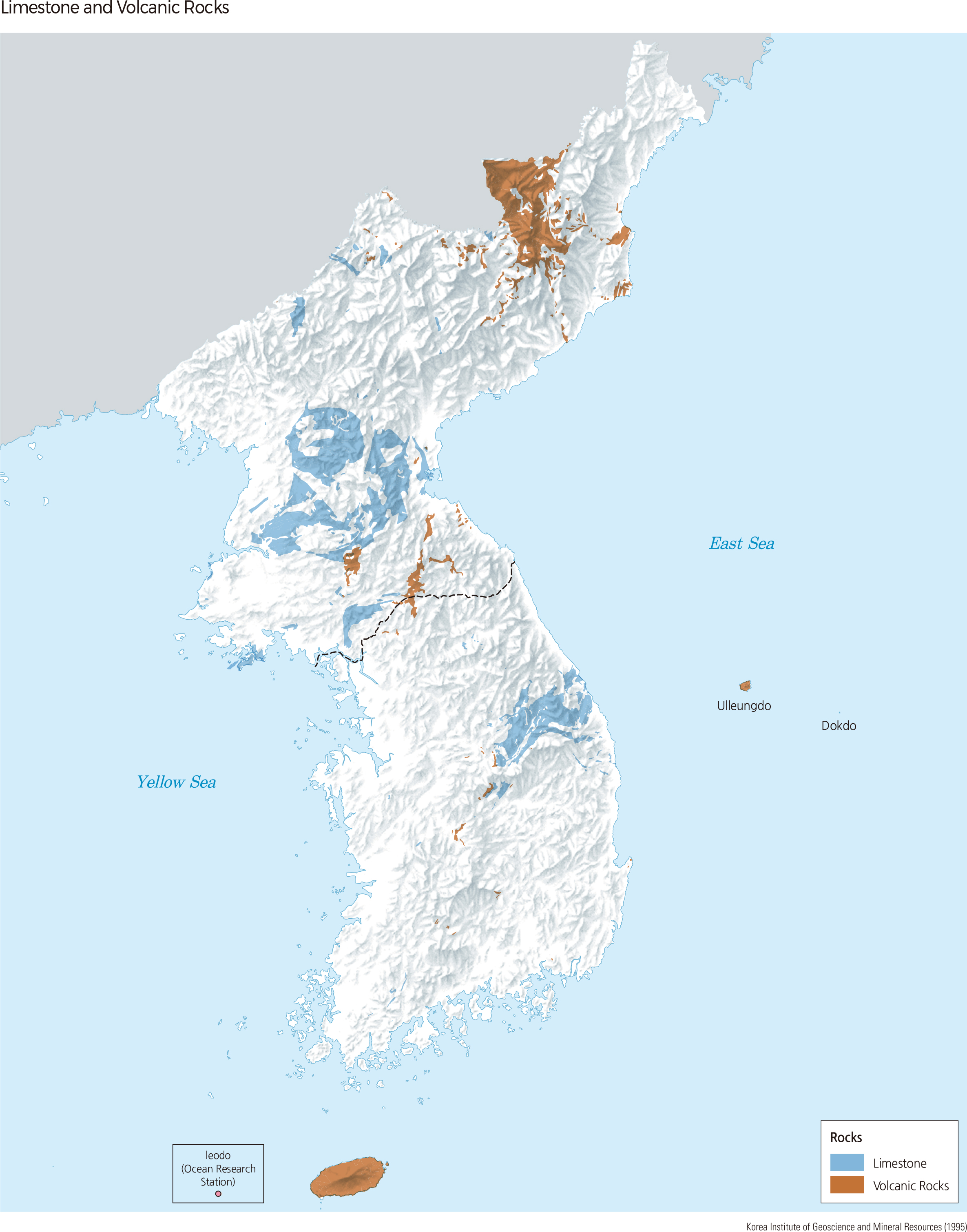

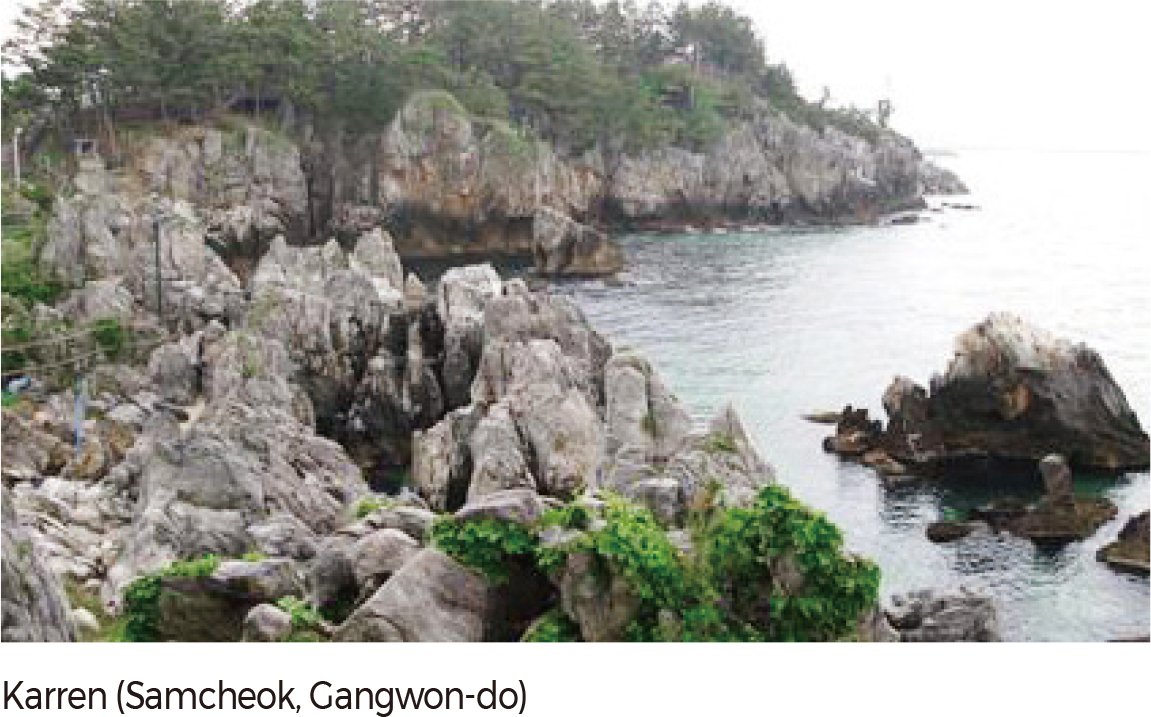

Ulleungdo and Dokdo are islands formed by the exposed peaks of a submarine stratovolcano. Unlike Jejudo, these islands have undergone extensive erosional processes resulting in hilly topography. Ulleungdo is a massive volcano that stands at over 3,000 m from the seafloor to its highest peak, Seonginbong (the depth of water is 2,200 m; Seonginbong is 987 m above sea level). During the Tertiary period, basal eruptions produced an aspite that stood over 2,000 m high on the eroded continental plate. At the end of the Pliocene, overall denudation resulted in a wave-cut terrace, on top of which alkaline lava formed the volcanic body that can be seen today. Limestone is found in two geological formations in Korea: the Pyeongnam Basin and the Okcheon Basin. Both basins were formed during the Cambro-Ordovician. While the Pyeongnam Basin in North Korea displays more Cambrian features, the Okcheon Basin in South Korea has more Ordovician characteristics. Karst topography is concentrated around Taebaeksan, including regions such as Pyeongchang, Jeongseon, Samcheok, Jecheon, Yeongwol, Taebaek, Danyang, and Munkyeong. In particular, Yeongwol and Danyang are Korea’s major limestone areas where notable features of karst–dolines (sinkholes), karrens, limestone caves–can be observed. Karrens are located in Hanbando-myeon of Yeongwol and Maepo-eup of Danyang, while dolines are commonly seen in Maepo-eup and Gagok-myeon of Danyang.

Karst topography can be categorized into three formations: concave features, convex features, and underground caves. Concave topography such as sinkholes, dolines, and uvalas emerges when acidic rain corrodes limestone or collapses limestone caves under the surface. This land is usually used for agriculture. On the other hand, convex topography refers to the features that remain after the dissolution of limestone, including flowstones, stalagmites, stalactites, and columns. These features, collectively known as karrens, are formed through the precipitation and recrystallization of calcium carbonate. Although large-scale karrens are not located on the Korean Peninsula, smaller features can be found around agricultural areas. Limestone caves develop as a result of groundwater runoff penetration below the surface. As the most well-known of the three types of karst topography, these caves often become tourist attractions. Prominent limestone caves in Korea include the Gosugul (Gosu Cave) of Danyang, the Gossigul (Gossi Cave) of Yeongwol, and the Hwanseongul (Hwanseon Cave) of Samcheok.

Paleochannels or abandoned channels are channels that cease to be part of an active river system. Paleochannels are ecological pathways that connect the land and river. They are spaces that contain clues that can indicate changes in the river channels and their neighboring areas. Today, paleochannels are destroyed or newly formed by human activities such as agriculture or other land use. Paleochannels are formed naturally, via neck-cutoff of incised meanders or free meanders, distributaries, and stream capture, or formed artificially, such as via channelization.

A total of 409 paleochannels have been identified in Korea. Of these, 321 formed naturally (266 by neck-cutoff of incised meanders, 38 by stream capture, and 17 by distributaries) and 86 formed artificially (5 by channelization of incised meanders, 55 by channelization of free meanders, and 28 by channelization of distributary channels).

Paleochannels created by neck-cutoff of incised meanders are well distributed throughout Korea, except on the extensive plain in the coastal area. The upstream of Nakdonggang, tributaries of Namhangang (Dalcheon and Pyeongchanggang), a tributary of Nakdonggang (Banbyeoncheon), a tributary of Bukhangang (Soyanggang), and Wangpicheon on the East Coast are examples of this kind of paleochannel.

Paleochannels by capture are easily found in the mountain areas experiencing active uplifts, such as Hangang, Nakdonggang, Geumgang, and Seomjingang. Distributary paleochannels are mainly found in drainage basins with extensive areas such as midstream and downstream of Hangang and Nakdonggang. Paleochannels created by channelizing free meanders are mainly found midstream and downstream of relatively large rivers such as Mangyeonggang, Yeongsangang, and tributaries of Yeongsangang (Sampocheon, Hampyeongcheon, and Gomakwoncheon) and Geumgang (Nonsancheon and Mihocheon). Geumhogang around Gyeongsan-si, Gyeongsangbuk-do, shows the most frequent distribution of paleochannels by channelization of distributaries. Agricultural land and forest mainly occupy the paleochannels formed by the neck-cutoff of incised meanders and by stream capture, while wetlands and water appear in the other types of the paleochannels.

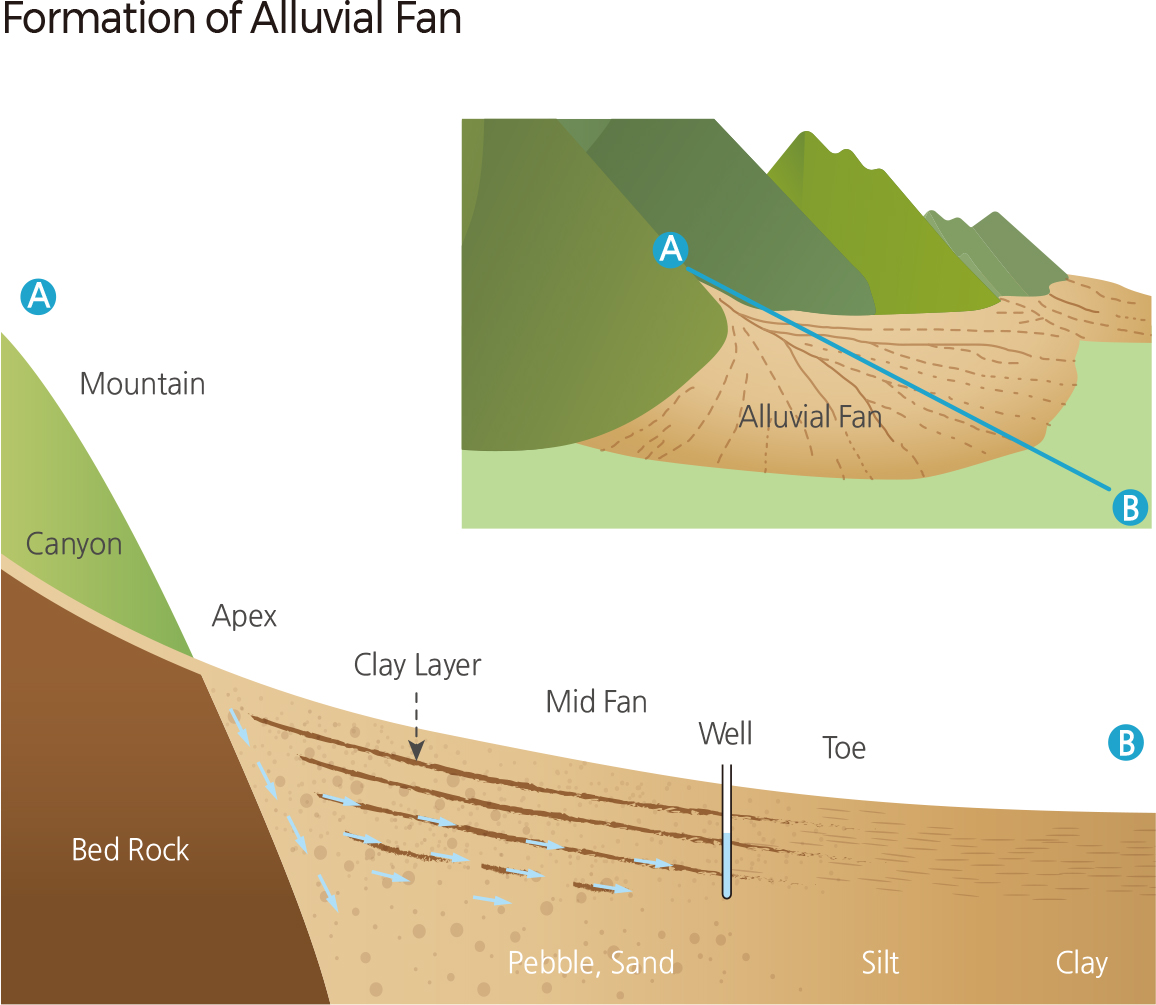

An alluvial fan is formed by the deposition of sediments at a valley mouth by a river flowing from a narrow valley in the mountain to a wide flat area. Alluvial fans can be found in almost all climatic zones, from low latitude tropical areas to high latitude periglacial areas and arid and semi-arid areas. Formation of an alluvial fan was thought to require a knickpoint. Recent studies have argued that channel change from a narrow valley to a wide flat area resulting in changes in discharge and flow velocity leads to the formation of an alluvial fan, whether there is a knickpoint or not.

Alluvial fans in Korea were interpreted as a piedmont or a pediment due to thin sediment and atypical form. Recent studies have reported several alluvial fans in Korea. The alluvial fan in Geumgwangpyeong is in Gangneung-si Gangwon-do; the one in Jecheon is in Jecheon-si, Chungcheonbuk-do. The alluvial fan in Angang is in Gyeongju; the one in Ipsil is in Gyeongju-si, Gyeongsangbuk-do. The alluvial fan in Sangcheon is in Ulju-gun, Ulsan while the one in Cheongdo is in Cheongdo-gun, Gyeongsangbuk-do.

The alluvial fan in Wolbae is in Dalseo-gu, Daegu and another one can be found in Jeokjung in Hapcheon-gun, Gyeongsangnamdo. Alluvial fans found at Cheoneunsa and Hwaeomsa in Guryegun, Jeollanam-do and at Sacheon and Samcheonpo in Sacheonsi, Gyeongsangnam-do were reported as the representative alluvial fans with an area of > 2 ㎢ in Korea.

Alluvial fans in Korea can be categorized into three types: fans by a small river flowing from a narrow mountain valley to the relatively extensive bottom of an erosional basin (Geumgwangpyeong, Jecheon, Cheongdo, Wolbae, and Jeokjung); fans by a tributary flowing to the extensive flood plain of a main river (Cheoneunsa, Hwaeomsa, Sacheon, and Samcheonpo); and fans by a small river laterally flowing to the interior area of a linear fault valley (Gyeongju, Angang, Ipsil, and Sangcheon).

Cultural heritage in Korea is classified into monuments, folklore, and tangible and intangible cultural heritage. Monuments bear great historic, cultural, scientific, aesthetic, or academic value, through which the history of a nation or the secrets to the creation of the earth can be identified or revealed.

Natural monuments mostly centered around animals or plants in the past. In recent years, various geomorphological and geological resources have been designated and managed as natural monuments. As of 2020, a total of 461 sites are designated as natural monuments, categorized as follows: cultural and historical heritage (monuments, folklore, life, history, and religion), bioscience heritage (typicality, taxonomy, chorology, biota, genetics, rareness, and specificity), geoscience heritage (paleobios, living organisms, natural phenomena, geomorphological and geological resources, and natural caves), cultural and natural heritage (landscape and scientific characteristics, and territorial symbolism), and natural science (special biota and marine biota).

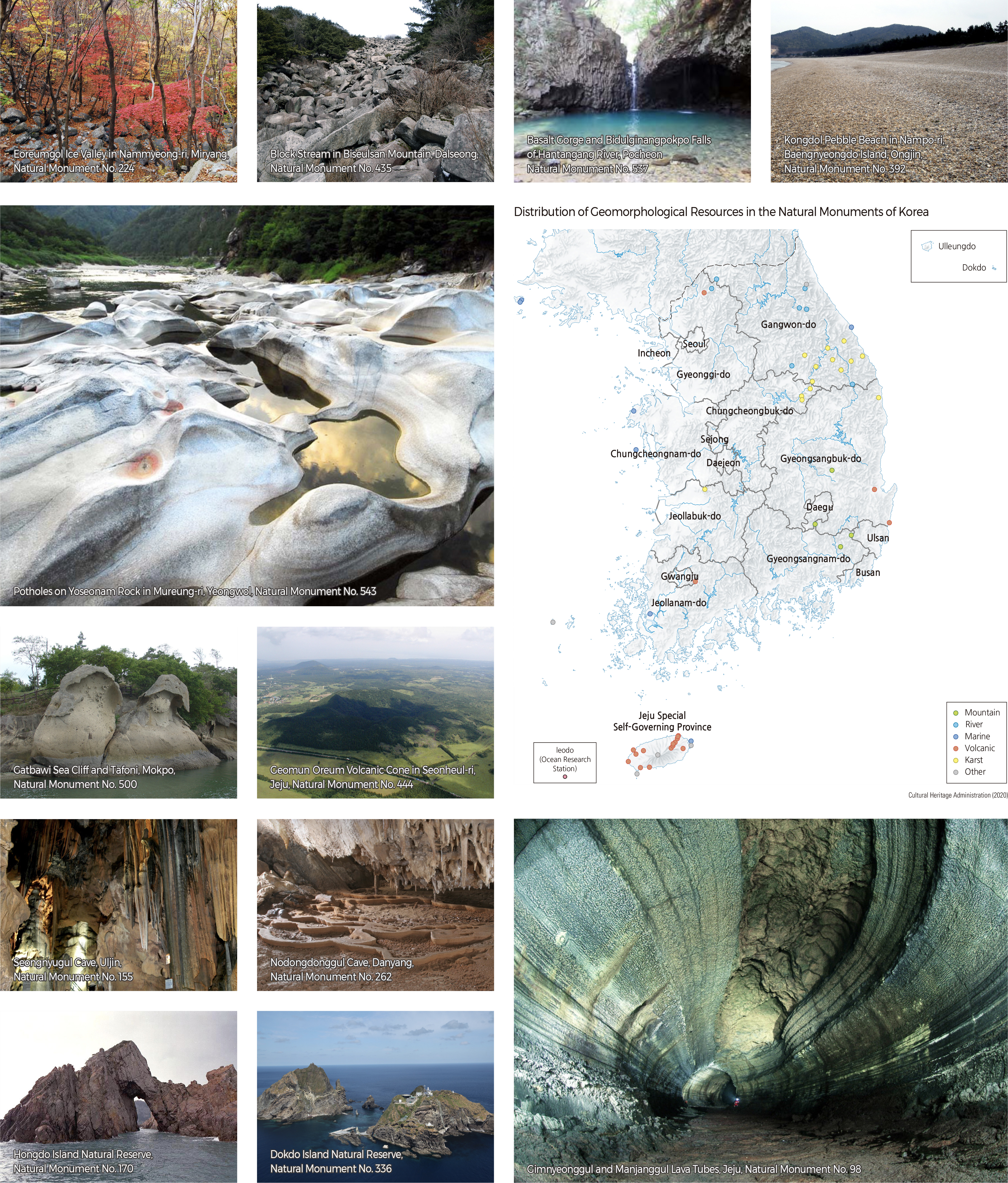

There are 56 geomorphological natural monuments in Korea, including mountain, fluvial, coastal, volcanic, karst, and other unique or complex landforms. There are four mountain landforms, including the Eoreumgol Ice Valley in Nammyeong-ri, Miryang-gun (Natural Monument No. 224) and a block stream on Biseulsan, Dalseong-gun (Natural Monument No. 435). There are seven fluvial natural monuments, including Basalt Gorge and Bidulginangpokpo Falls of Hantangang, Pocheon-gun (Natural Monument No. 537) and potholes on Yoseonam Rock in Mureung-ri, Yeongwol-gun (Natural Monument No. 543). There are seven coastal natural monuments, such as Kongdol Pebble Beach in Nampo-ri, Baengnyeongdo, Ongjin-gun (Natural Monument No. 392) and Gatbawi Sea Cliff and associated tafone in Mokpo (Natural Monument No. 500). There are 18 volcanic natural monuments, including the Gimnyeonggul and Manjanggul lava tubes in Jejudo (Natural Monument No. 98) and the Geomunoreum volcanic cone in Seonheul-ri, Jejudo (Natural Monument No. 444). There are 14 karst natural monuments, including Seongnyugul Cave, Uljin-gun (Natural Monument No. 155) and Nodongdonggul Cave, Danyang-gun (Natural Monument No. 262). Hongdo Island Natural Reserve (Natural Monument No. 170) and Dokdo Island Natural Reserve (Natural Monument No. 336) are natural monuments classified as complex landforms.

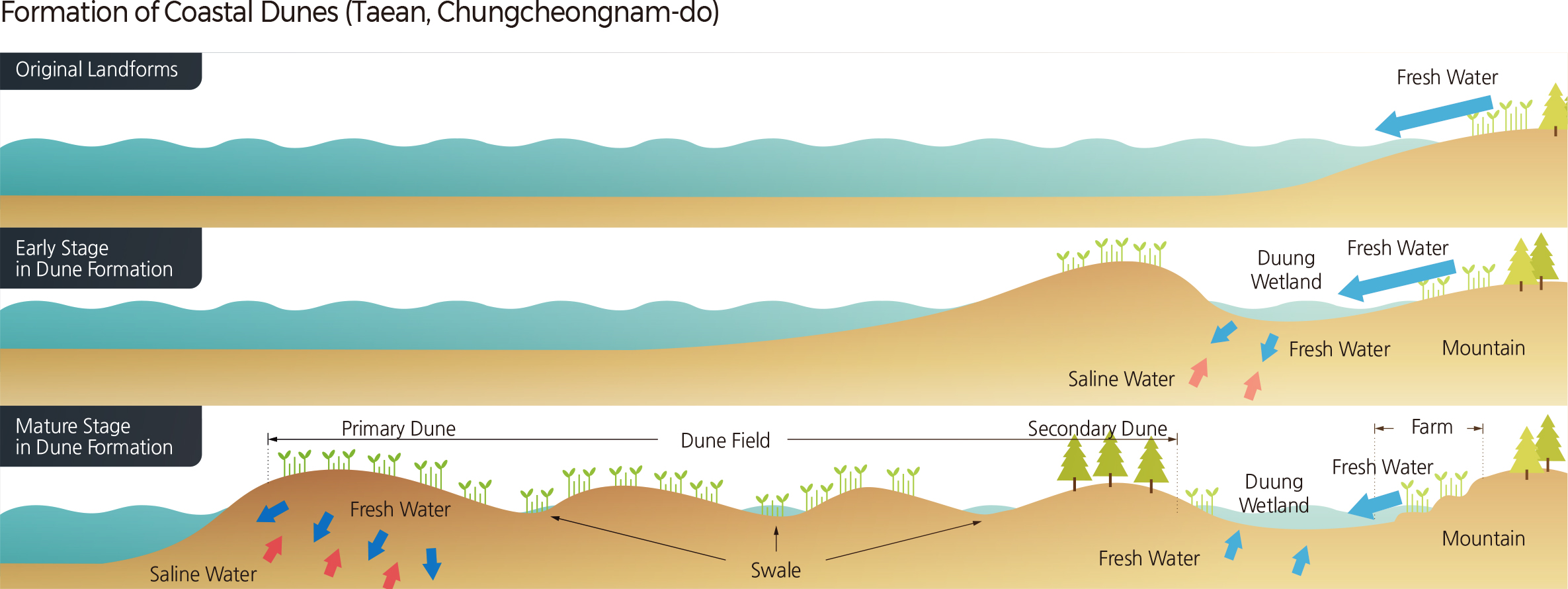

A coastal sand dune is a hill consisting of sand blown from a sandy beach and deposited behind the beach. It is located in a transitional zone between terrestrial and marine environments. Thus, a coastal sand dune is ecologically important, serving as a natural breakwater to reduce the intensity of natural hazards and their damage. Coastal sand dunes are sensitive to environmental changes. When the coastline retreats due to sea-level rise, coastal sand dunes also retreat. Therefore, these dunes not only maintain the coastal landform but also contain information on paleoenvironmental changes.

A total of 199 coastal sand dunes have been identified. Sixty-three coastal sand dunes are located in Jeollanam-do, which has a complex and long coastline and many islands, including the Bigeummyeongsan Dune in Jidang-ri, Bigeum-myeon, Sian-gun and the Geumilmyeongsa Dune in Wolsong-ri, Geumil-eup, Wando-gun. Chungcheongnam-do has the second most coastal sand dunes (45 dunes), including the Woncheong Dune in Woncheong-ri, Nam-myeon, Taean-gun. Thirty-one coastal sand dunes are found in Gangwon-do where sand beaches are well developed, including the Yangyangdongho Dune in Dongho-ri, Yangyang-eup, Yangyang-gun. Seventeen coastal sand dunes were identified mostly on islands in Incheon, including the Seopori Dune in Seopo-ri, Deokjeok-myeon, Ongjin-gun. There are 14 in Jeju Special Self-Governing Province, including the Hyeopjae Dune in Hyeopjae-ri, Hallim-eup, Jeju-si, and 12 in Gyeongsangbuk-do, including the Goraebul Dune in Byeonggok-myeon, Yeongdeok-gun. Eight coastal sand dunes are found in Jeollabuk-do, including the Gochangmyeongsa Dune in Sangha-myeon, Gochang-gun.Busan and Gyeonggi-do have four and three coastal sand dunes, respectively. Only two coastal sand dunes are located in Namhae-gun, Gyeongsangnam-do.

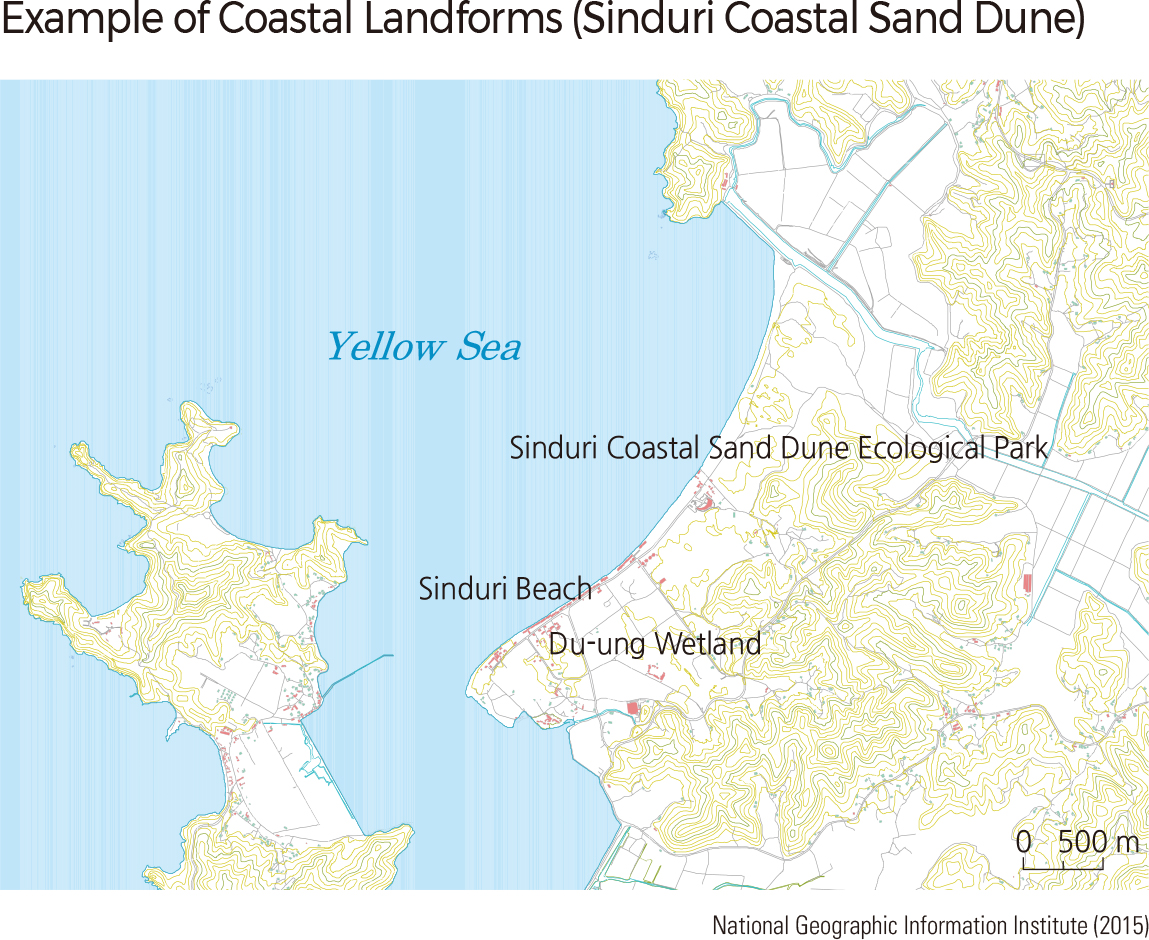

Eighty-one of these 199 dunes are distributed in island areas, including Jejudo, and the rest are along the Peninsula’s coast. Sinan-gun, Jeollanam-do, has the most coastal sand dunes (30 coastal sand dunes), followed by Taean-gun (29 coastal sand dunes), Chungcheongnam-do. The Sinduri Dune in Sindu-ri, Wonbuk-myeon, Taean-gun, Chungcheongnam-do is the most extensive coastal sand dune at approximately 2.01 ㎢, followed by the Hyeopjae Dune (1.80 km2) in Hyeopjae-ri, Hallim-eup, Jeju-si, Jeju Special Self-Governing Province. Most of the coastal sand dunes in Korea are less than 1 ㎢ in size. |