English I 2019

North Korea’s economy is a centrally planned and unified system in which the State Planning Commission of the central government announces economic development plans and strictly controls smaller economic units, such as regional governments, factories, and companies.

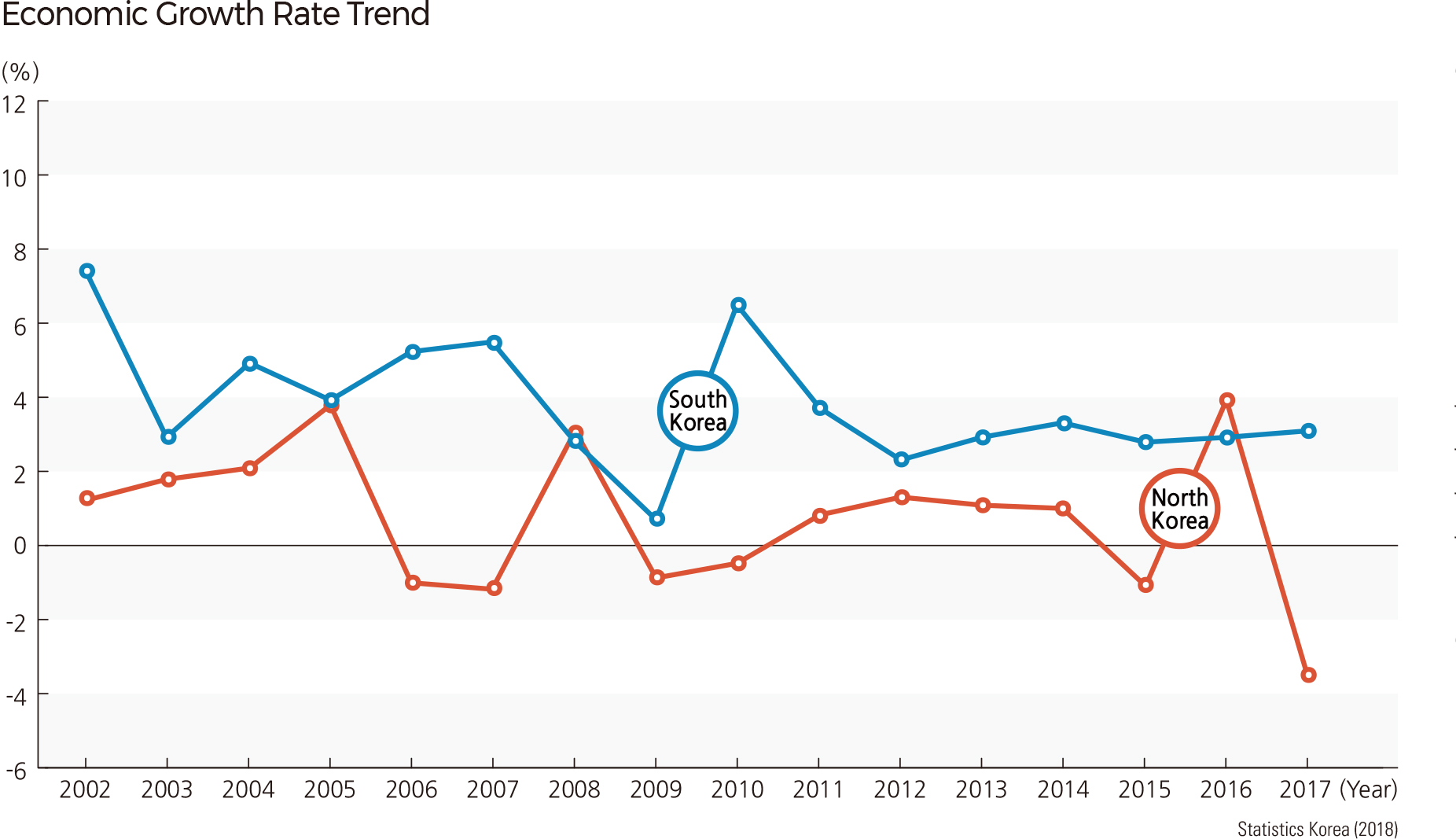

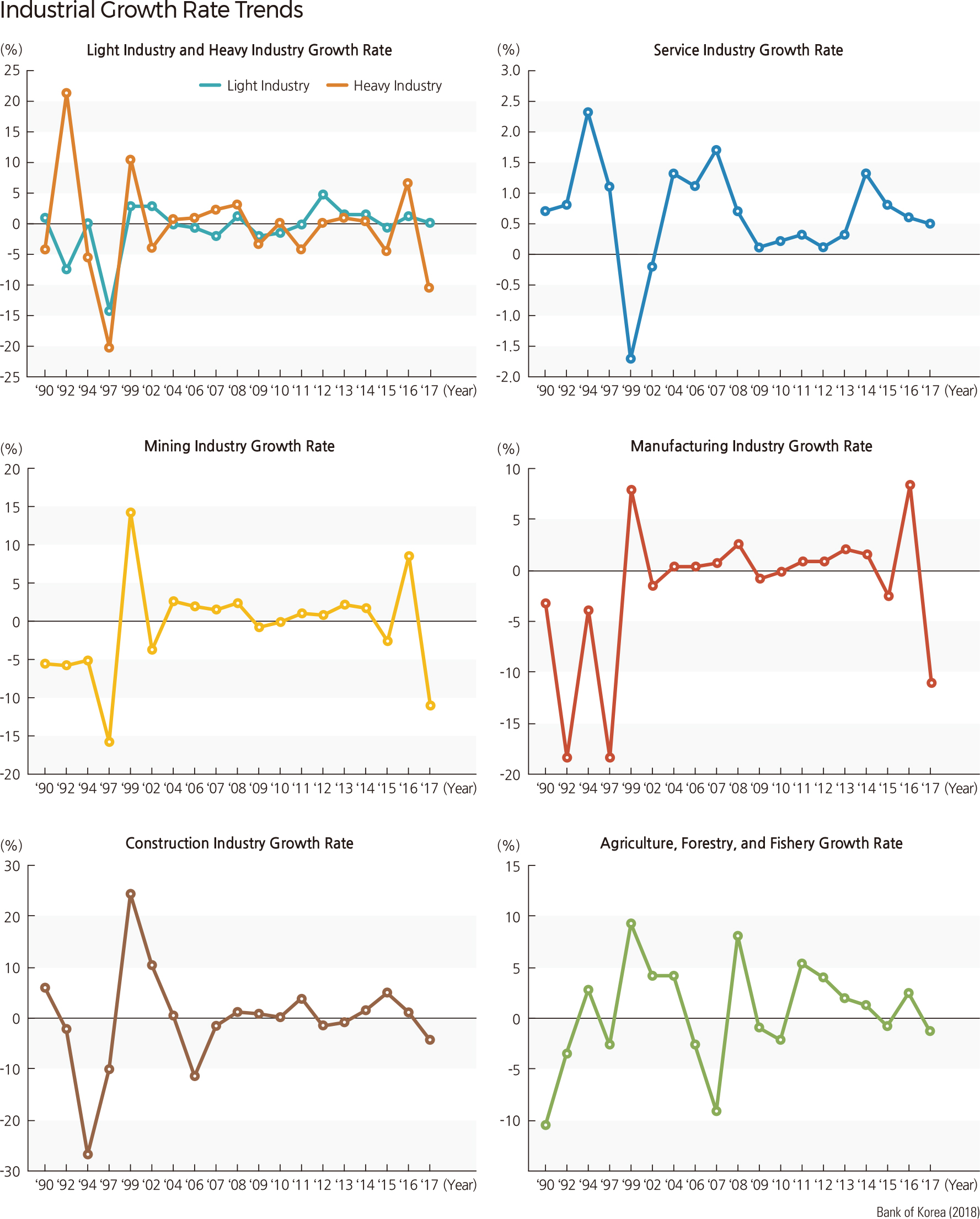

Along with a centrally planned system, another important feature of North Korea’s economy is that the country included plans to assign top priority to develop heavy industry with parallel developments in agriculture and light industry. Due to the lack of capital and resources, however, heavy industry was favored over light industry and agriculture. With the collapse of communist governments around the world during the 1990s, the problem of favoring heavy industry and ignoring agriculture and light industry became serious, and it led to financial difficulties and food shortages in the mid-1990s. The North’s economy began to recover after 1999, but it has experienced an average annual negative growth rate since 2006.

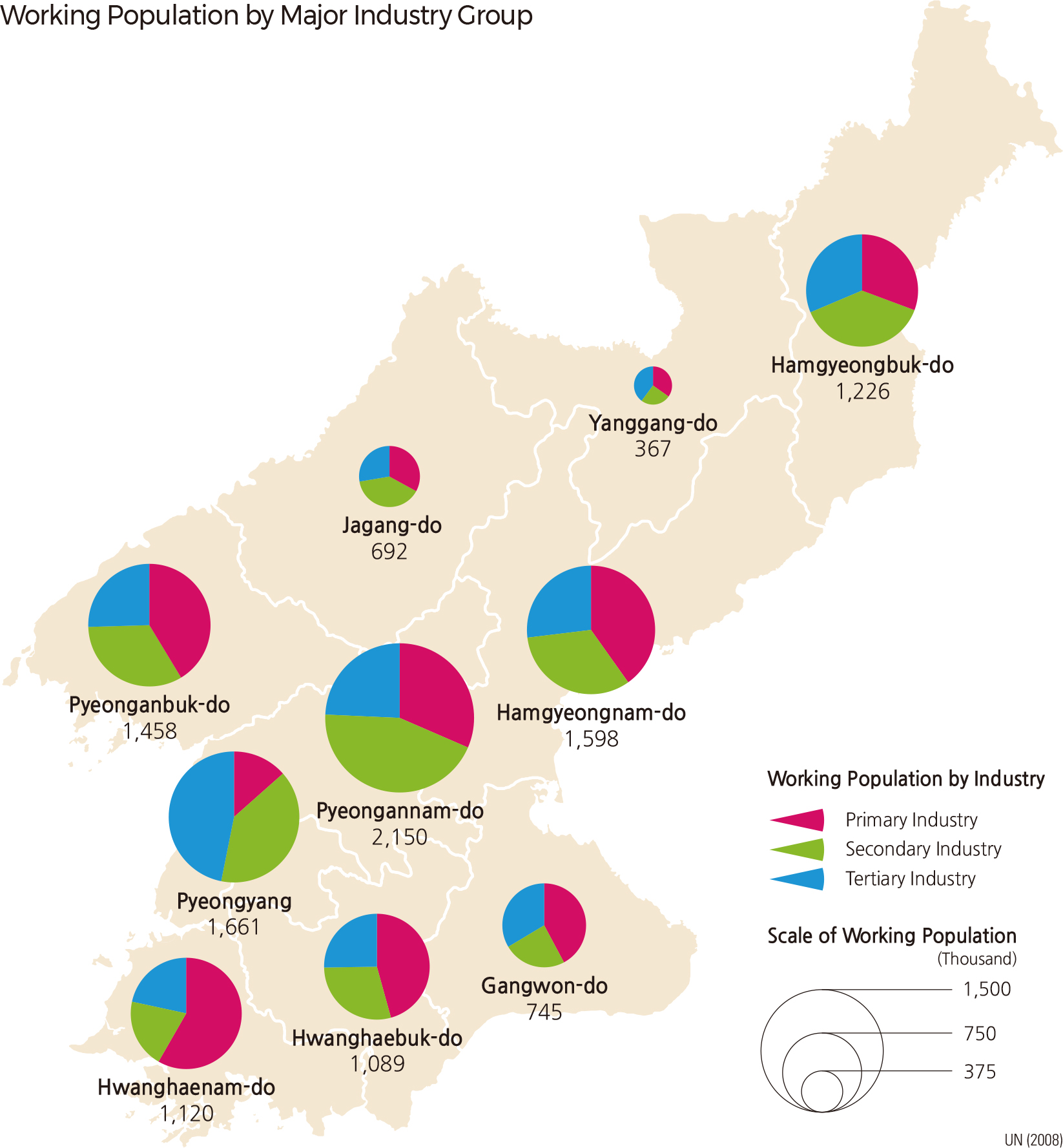

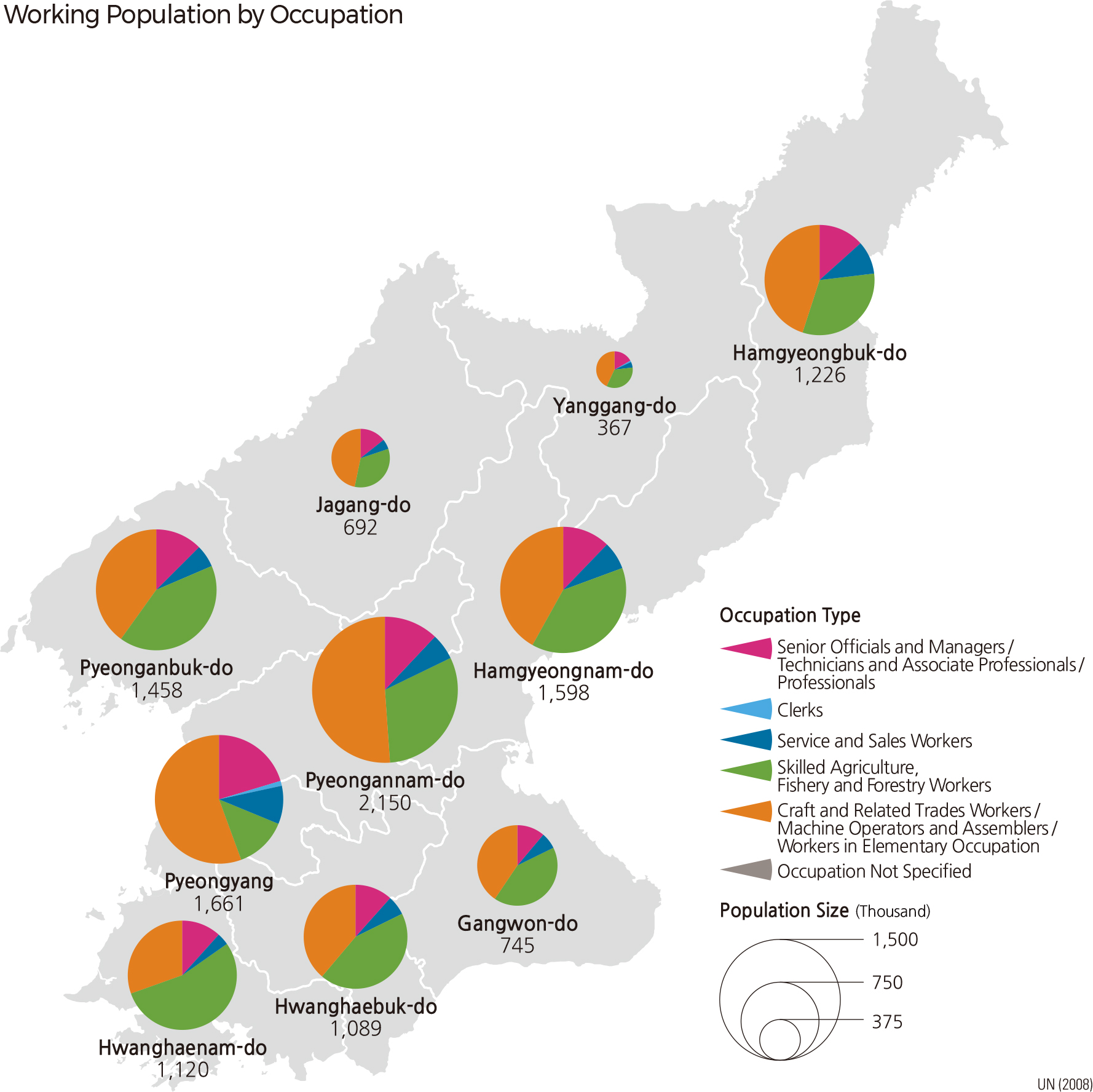

As of 2008, 36% of North Korea’s population was working in primary industries, 34.3% in secondary industries, and 29.6% in tertiary industries. As for Hwanghaenam-do and Hwanghaebuk-do, the rice bowl of North Korea, the largest share of the population works in primary industries, with a rate of 58.1% and 45.6%, respectively. In Pyeongannam-do, the largest proportion of people (44.3%) is laboring in secondary industries as this province is home to the Pyeongnam South Coalfield and Pyeongnam North Coalfield, which collectively boast the largest coal deposits in North Korea. In addition, major industrial facilities, such as Cheollima Steelworks, the Daean heavy machinery factory, and the Nampo smelting factory, are located in the city of Nampo. North Korea’s service industry has generally posted slow growth, except in Pyeongyang.

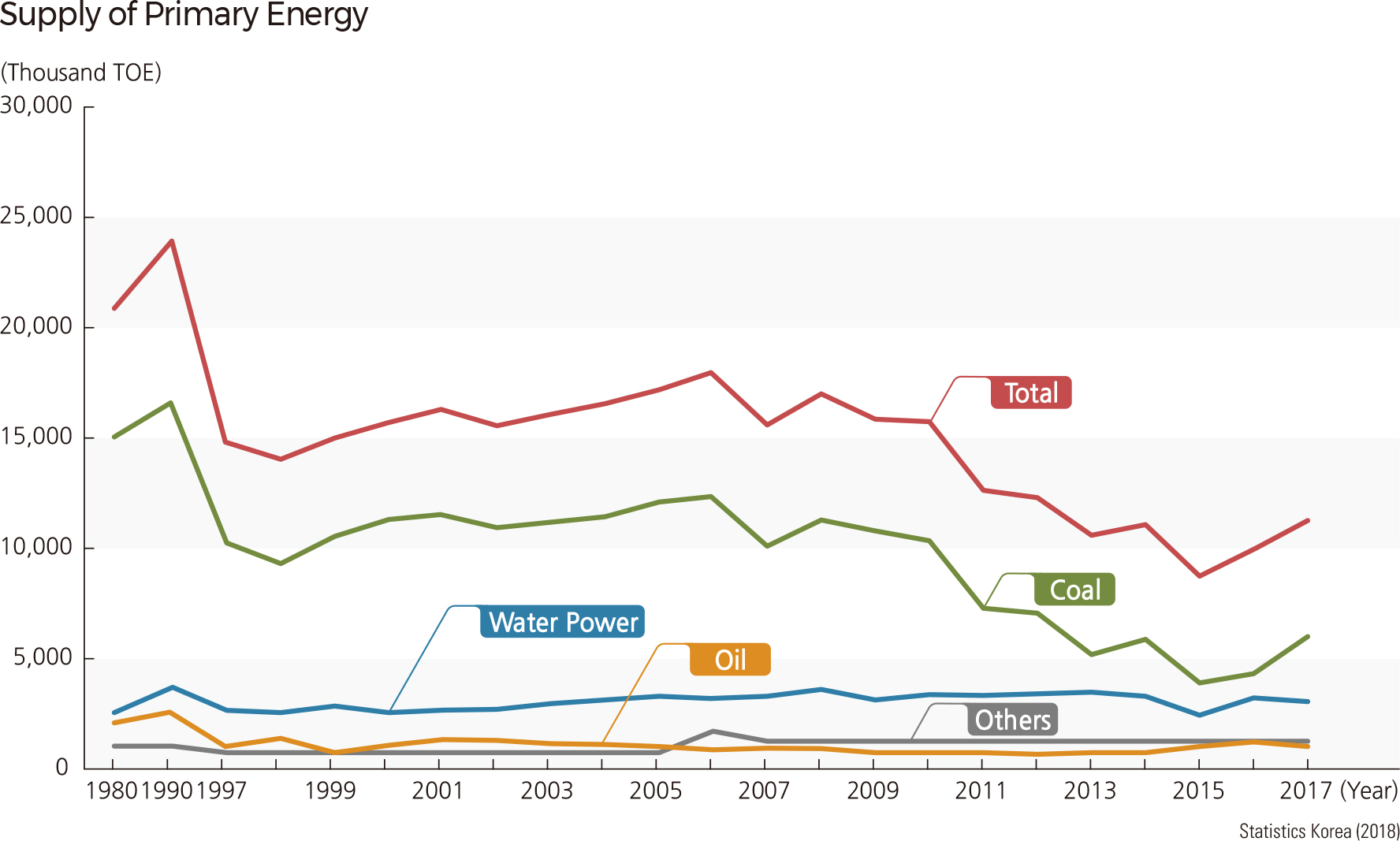

North Korea’s energy supply still relies heavily on coal, but it decreased from 70.2% in 2005 to 43.2% in 2016. On the other hand, hydraulic power almost doubled from 17.6% in 2006 to 32.3% in 2016. Oil imports fluctuated from 4.4% to 11.8%, due to external factors such as international sanctions and the Sino-DPRK relationship. In the case of North Korea’s food supply and demand, its food shortage has decreased in comparison to the mid- and late 1990s, when it suffered from a severe food crisis. Since 2013, North Korea has maintained agricultural production at an average of 4.8 million tons every year, which has lowered the annual average food deficit to 0.53 million tons. However, as the ratio of recent year-to-year food production versus demand rose from 80% to 90%, it is too early to tell if the food supply has stabilized.

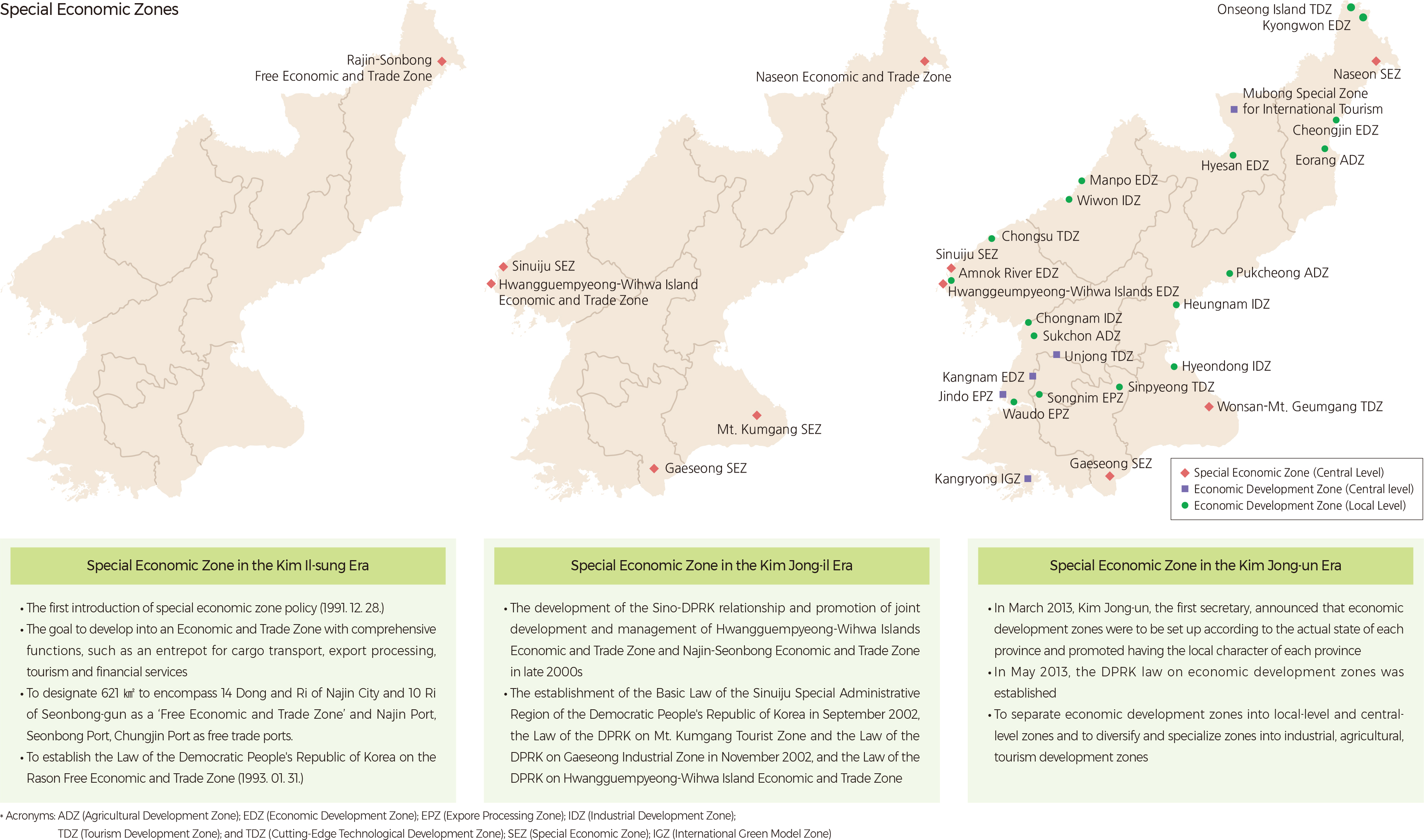

One of North Korea’s most important goals is a self-sufficient economy, but unfortunately, this imperative led it to underestimate the importance of economic cooperation with foreign countries. As a result, North Korea imported a minimum amount of indispensable raw materials, mostly from former socialist countries. When North Korea realized this policy’s weakness, it began to work on economic cooperation with other foreign countries, a process North Korea has engaged in since the 1970s. In 1991, the first special economic zone was established in Najin-Seonbong to attract foreign capital. In September 2002 under the Kim Jong-il regime, Sinuiju was designated as a special administrative zone, and in October of that year, the Gaeseong Industrial Complex was promoted to a special economic zone, followed by the Geumgangsan Mountain area in November.

In January 2010, North Korea promoted the Najin-Seonbong Special Economic Zone, whose development was slow due to economic sanctions because of North Korea’s nuclear tests, to a Special City. In June 2011, along with the Najin-Seonbong Special Economic Zone, the North announced the joint development and management of the Hwangguempyeong-Wihwado Special Economic Zone near the Amnokgang River.

The Special Economic Zones policy has been more aggressively promoted under the Kim Jong-un regime, and it is now expanding across the country. With the enactment of the “Economic Development Zone Act,” North Korea announced 13 economic development districts to attract foreign investment, with Sinuiju being designated as a new special economic zone. In July 2014, North Korea designated six more economic development zones, including Unjong, a cutting-edge technological development zone. Subsequently in April 2015, it added Mubong Special Zone for International Tourism, followed by Kyongwon Economic Development Zone (October 2015), and Kangnam Economic Development Zone (December 2017). Twenty-seven special economic zones are divided into central government-level economic zones and local-level economic zones and are specialized in industrial, agricultural, tourism, export processing, and high-technology realms. However, North Korea’s economic policies have not been smooth due to international sanctions as a consequence of nuclear and missiles tests.

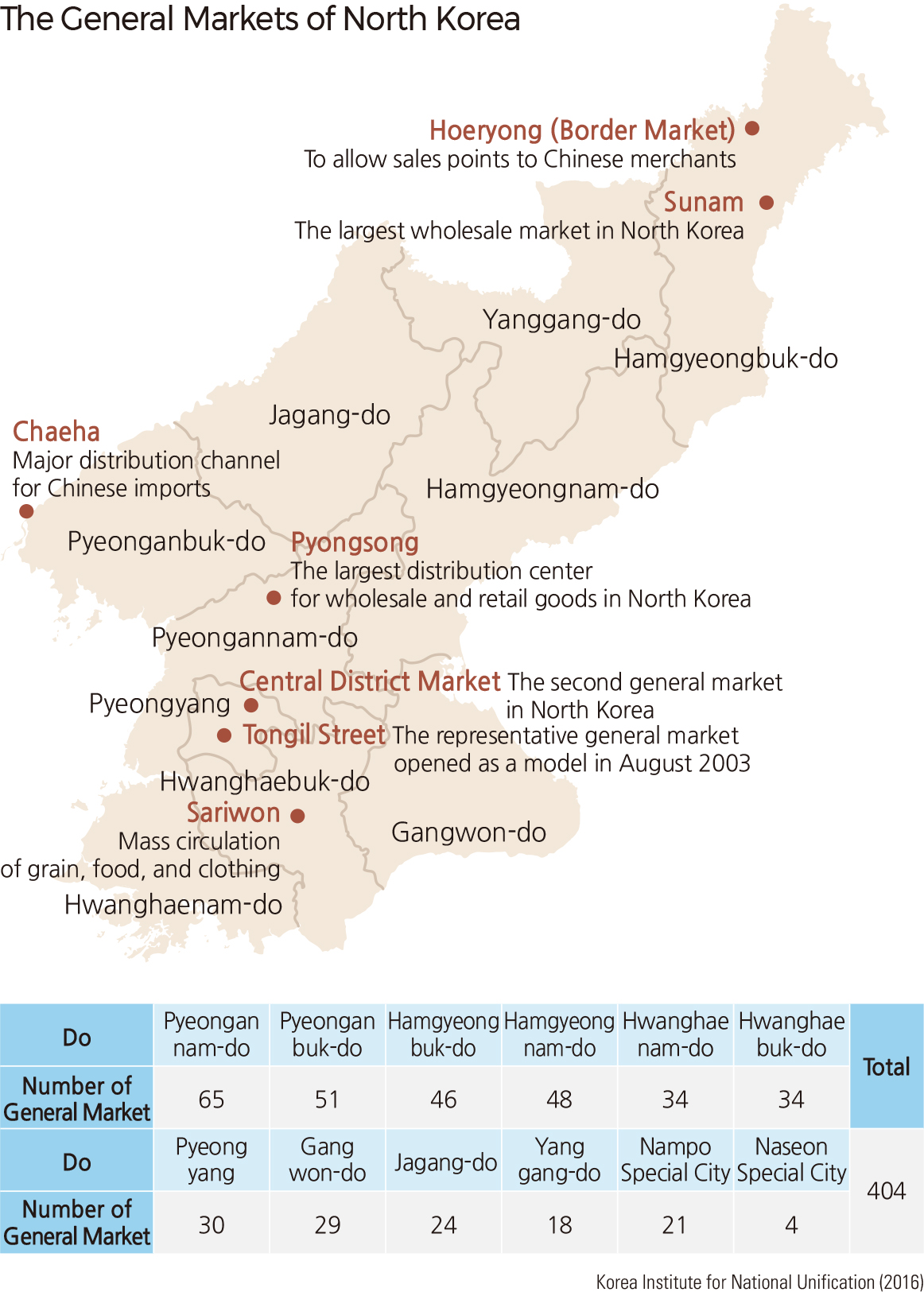

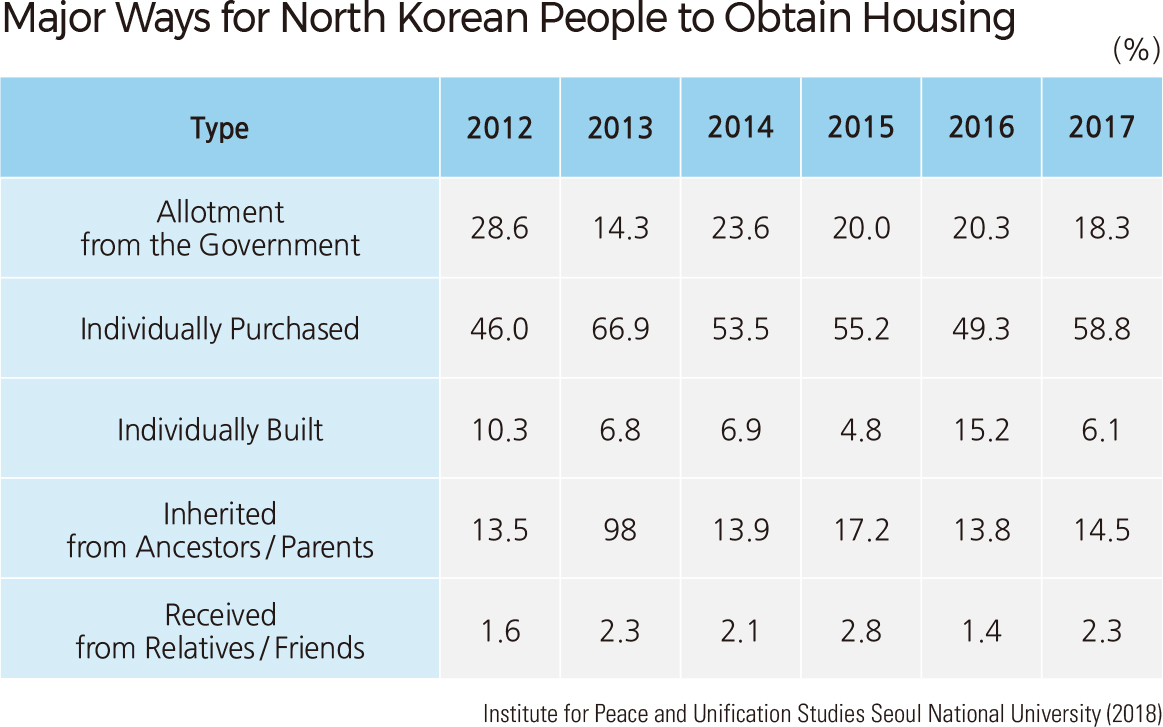

On July 1, 2002, North Korea partially introduced some elements of a market economy into the existing centralized planning economy through the adoption of the Economic Management Improvement Measures. While it enforced measures such as a crackdown on commercial activities and closure of general markets in order to prevent excessive marketization, the North Korean government has adopted some policies since February 2010 to relax the market activities. This helped North Korea’s marketization expand into official economic realms and increase its number of markets. As of 2018, there were 460 general markets across the country. In addition, a newly moneyed class called ‘donju’ is emerging with the accumulation of commercial capital. This group of people is expanding their economic influence, from the circulation of a variety of goods through official trade, to border trade or smuggling, to the construction industry, such as building and trading apartments. |