THE NATIONAL ATLAS OF KOREA 2024

|

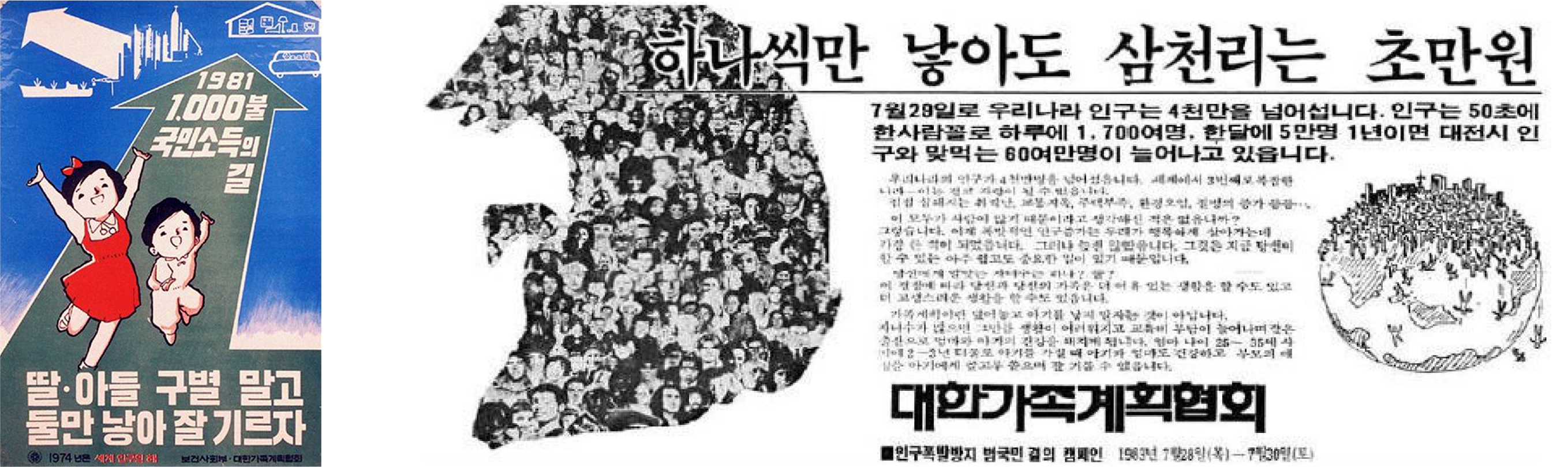

Low Birthrate and Local Extinction

The average annual population growth rate (based on the total population) of South Korea, which was around 2–3% until the 1960s, was higher than the global average and the OECD average. However, it declined sharply from the 1970s to the mid-1980s and has continued to decrease to the present day (0.14% in 2020). Analyzing the five-year average annual chan ge rate of the total population, there was a 1.01 percentage point decrease between 1980–1985 and 2005–2010. During The average annual population growth rate (based on the total population) of South Korea, which was around 2–3% until the 1960s, was higher than the global average and the OECD average. However, it declined sharply from the 1970s to the mid-1980s and has continued to decrease to the present day (0.14% in 2020). Analyzing the five-year average annual change rate of the total population, there was a 1.01 percentage point decrease between 1980–1985 and 2005–2010.

|

Total Fertility Rate of South Korea

South Korea’s ongoing ultra-low birth rate, which began in 2002, ranked lowest among the 38 OECD countries and among 217 countries globally in 2021. The total fertility rate was 0.81 in 2021, significantly lower than the global average of 2.3 and the OECD average of 1.58. Excluding city-states, South Korea is the first country in the world to record a total fertility rate below 1.0. Due to low birth rates, the population has been naturally declining since 2020, and the demographic structure has shifted from a pyramid to a diamond shape due to a sharp decrease in the youth population.

According to population trend statistics, except for the early 1980s and mid-1990s, the number of births has been steadily decreasing. The number of births, which was around 1 million in 1970, took about 30 years to fall below 500,000 (2002: 496,000) and about 20 more years to be nearly halved again (2020: 272,000). The year-overyear growth rate of births showed repeated increases and decreases from 1970 to 2015, but since 2015, a continuous decline has been observed. The number of deaths remained relatively stable from the mid-1980s to the late 2000s but increased between 2010 and 2020. Unlike births, the number of deaths generally shows an increasing trend. The natural population increase, calculated by subtracting the number of deaths from births, has continued to decline, reaching negative growth in 2020, where the number of deaths exceeded births (272,000 births vs. 304,000 deaths).

The average annual population growth rate (based on the total population) of South Korea, which was around 2–3% until the 1960s, was higher than the global average and the OECD average. However, it declined sharply from the 1970s to the mid-1980s and has continued to decrease to the present day (0.14% in 2020). Analyzing the five-year average annual chan ge rate of the total population, there was a 1.01 percentage point decrease between 1980–1985 and 2005–2010. During The average annual population growth rate (based on the total population) of South Korea, which was around 2–3% until the 1960s, was higher than the global average and the OECD average. However, it declined sharply from the 1970s to the mid-1980s and has continued to decrease to the present day (0.14% in 2020). Analyzing the five-year average annual change rate of the total population, there was a 1.01 percentage point decrease between 1980–1985 and 2005–2010.

Current Status and Characteristics of Low Birth Rates and Aging Population

As of 2023, South Korea is experiencing an unprecedented ultra-low birth rate, with a total fertility rate of 0.72, ranking lowest among OECD countries and globally. Furthermore, the decline in the total fertility rate has occurred at a faster pace compared to other countries, making it the steepest globally.

To analyze the causes of the low birth rate, government and private research institutions have used various standards and statistics. Three main statistical causes of the declining birth rate have been identified: 1) a decrease in marriage rates, 2) an increase in childless marriages, and 3) a decrease in the average number of children among married women with children.

South Korea’s crude marriage rate (number of marriages per 1,000 people) has been steadily decreasing since 2012. The number of marriages dropped sharply from about 327,000 in 2012 to about 193,000 in 2023. According to the National Statistical Office’s social survey, the main reasons for not getting married include economic burdens related to marriage, childbirth, and childcare, and employment instability, reflecting social and economic reasons.

In a 2022 social perception survey by the National Statistical Office, more than half (53.5%) of young people responded that it is not necessary to have children after marriage, with women (65%) more likely than men (43.3%) to think that having children after marriage is not necessary. Also, younger age groups tend to have a more favorable perception of childlessness.

The persistent low birth rate has rapidly aged the population structure, resulting in South Korea having an extreme demographic structure characterized by ultra-low birth rates and a super-aged society. The population pyramid of South Korea in 2020 shows the middle-aged (35–49) and older middle-aged (50–64) groups made up about 56% of the total population. The median age of the total population, including foreigners, is 45.7, indicating a high level of aging in South Korea. Generally, a society is considered aged when the proportion of people aged 65 and over exceeds 14%, and older adults already comprise about 19.4% of South Korea’s population, classifying it as an aged society. The proportion of infants (0–4 years) and children (5–14 years) combined is lower than that of the older adult population (about 2.5% and 9%, respectively). If the low birth rate and reluctance to marry continue to worsen, South Korea may eventually become a super-aged society with more than 20% of its population aged 65 and over. By gender, a male-dominant phenomenon

is observed in the 0–59 age group, while a female-dominant trend is seen in the 60 and older age group.

According to the “2023 Population and Housing Census Results,” the aging index in 2023 was 171.0, up 14.9 from 2022 (1.71 older adults per youth in South Korea). The aging index exceeded 100 for the first time in 2016 (100.1) and has been increasing annually since 2018. The population aged 65 and over is approaching 10 million, with an increase of 462,000 from the previous year in 2023, reaching 9.609 million. The old-age dependency ratio (the number of people aged 65 and over per 100 working-age people) increased to 26.3. In contrast, the population aged 0–14 decreased by 241,000 (4.1%) to 5.619 million from the previous year. Due to the impact of population aging, the median age of the total population increased by 0.6 years to 45.7. The number of single older adult households reached 2.138 million, accounting for 9.7% of all households. The number of older adult households increased by 8.3% from the previous year, while the number of single older adult households increased by 7.2%. Single-person households accounted for 35.5% of all households, marking a record high due to aging and household diversification.

Such an abnormal demographic structure can lead to household income inequality arising from differences in the number of children or the age of children. The decline in the proportion of the working-age population and the increase in the oldage dependency ratio due to aging can hinder national growth in the long term. Additionally, the ongoing trend of low birth rates and aging increases South Korea’s ranking in terms of the proportion of the older adult population compared to other OECD countries.

Furthermore, a decrease in the school-age population could lead to the collapse of educational infrastructure, and from a security perspective, a decline in conscription resources may make it challenging to maintain standing forces. In addition, the population crisis ultimately leads to the extinction of local areas, necessitating a national-level response. The government announced the establishment of the Population Strategy Planning Department in June 2024 to implement specific low birthrate measures and declared the world’s lowest total fertility rate in 2023 a national emergency

With the ongoing low birth rate and declining fertility rate, concerns about the extinction of regions are increasing. Recent research and surveys indicate that local extinction is accelerating due to the intensification of population outflow caused by social factors. In response, the government and academia have been using three indices—Masuda’s Local Extinction Risk Index, the K-Local Extinction Index, and the Population Decline Region Index—to assess the extent of local extinction and devise appropriate countermeasures.

Masuda’s Local Extinction Risk Index

Masuda’s Local Extinction Risk Index, announced in Japan in 2014, measures the degree of local extinction based on the population of women of childbearing age and the older adult population (women aged 20–39/older adult population aged 65 or older). This index explains the risk level of regional extinction from a demographic perspective. The decline in the population of young women, who account for 95% of total births, leads to a decrease in population reproduction capacity, which results in a decrease in the total population. In other words, if the outflow of young women lowers the fertility rate and the number of older adult deaths within the region increases, the total population in a specific area will quickly decrease, leading to a stage of local extinction.

If the index value is between 0.5 and less than 1.0, the area is classified as a caution region for population extinction. If the value is between 0.2 and less than 0.5, it is classified as a risk region, and if it is less than 0.2, it is considered a high-risk region for population extinction.

K-Local Extinction Index

While Masuda’s Local Extinction Risk Index focuses on natural factors of population reproduction capacity, in Korea, it is difficult to explain the phenomenon of local extinction solely through Masuda’s logic due to the continuous outflow of the population caused by various social factors.

In 2022, the Korea Institute for Industrial Economics & Trade (KIET) developed the K-Local Extinction Index, which reflects the realities of the regional economy based on Korea’s population and economic structure.

According to KIET, interregional population movements in Korea’s local extinction areas are closely related to regional economic mechanisms such as income or jobs. The index is calculated based on four indicators: (1) innovation activities, (2) industrial structure advancement, (3) high-value-added enterprises, and (4) regional growth.

The indicator related to innovation activities uses per capita R&D expenditure, which is calculated based on the annual technology development expenditure spent in the region divided by the total population.

The indicator for checking the advancement of the industrial structure uses the All-Industry Diversity Index, which minimizes distortions that may be caused by the predominance of a specific industry in a particular region.

The indicator representing high-value-added enterprises uses the ratio of knowledge industries to total businesses, which is also used to prevent imbalances that may manifest when spatial deviations occur by industry and by region.

The last indicator of regional growth is not easily explained by a single indicator; therefore, three indicators—number of employees per 1,000 people, gross regional domestic product (GRDP) per capita, and population change rate—are used to comprehensively determine employment conditions, income, and population changes.

Population Decline Region Index

Population decline regions designated under Article 2 of the Special Act on Local Autonomy and Regional Balance Development are designated after deliberation by the Ministry of the Interior and Safety, related agencies, and the Regional Era Committee Population decline regions are selected based on a total of eight population decline index indicators: (1) annual average population growth rate, (2) population density, (3) net migration rate of young people, (4) daytime population, (5) aging ratio, (6) youth ratio, (7) crude birth rate, and (8) fiscal self-reliance rate.

According to Masuda’s Local Extinction Risk Index evaluated in 2023, 157 out of 250 cities, counties, and districts were designated as local extinction risk areas. According to the K-Local Extinction Index in 2022, 116 areas were designated, and a total of 89 areas were designated as population decline regions according to the Population Decline Region Index in 2021. Among these, 84 places were designated as risk areas by all three indices.

Local Extinction Risk Areas

Based on population data, there were no local extinction risk or high-risk areas in 1980 and 1990, but the number of these areas increased sharply between 2000 and 2020. During the same period, the number of risk areas increased by about 2.4 times (29 in 2000 to 70 in 2020), and high-risk areas increased by 1.4 times between 2010 and 2020 (27 in 2010 to 38 in 2020). Based on the 2023 population, there are currently 78 risk areas and 79 high-risk areas, indicating a further increase in the risk of local population extinction.

According to Masuda’s Local Extinction Risk Index calculated based on 2023 population data, a total of 18 municipalities in non-metropolitan or metropolitan cities were not classified as risk or high-risk areas nationwide, including Heungdeok-gu and Cheongwon-gu in Cheongju, Dongnam-gu and Seobuk-gu in Cheonan, Asan City, Gyeryong City, Wansan-gu and Deokjin-gu in Jeonju, Gwangyang City, Nam-gu and Buk-gu in Pohang, Gumi City, Gimhae City, Geoje City, Yangsan City, Uichang-gu and Seongsan-gu in Changwon, and Jeju City. These results indicate that the risk of local extinction is relatively rapidly increasing in areas outside the metropolitan area. Similar results can be seen in the map results of the Population

Decline Region Index and the K-Local Extinction Index.

As of 2024, there are no residents in Jinsa-myeon in Paju, Gyeonggi Province; Geundong-myeon, Wondong-myeon, Wonnam-myeon, and Imnam-myeon in Cheorwon County, Gangwon Province; and Sudong-myeon in Goseong County, Gangwon Province. These areas, adjacent to the civilian control line, currently have no registered residents. In addition, even in Busan, Daegu, Gwangju, Daejeon, Ulsan, and Incheon, and Seoul, administrative districts that have entered the extinction risk phase exist, indicating that the risk of local extinction has started nationwide, including urban areas.

In areas with a high risk of extinction, birth rates are very low, and death rates are high. Since 2005, the government has diagnosed the natural decline of the population as the main cause of local extinction and has been promoting measures to respond to low birth rates. However, recent analysis of population increase and decrease factors indicates that the main cause of local extinction is population outflow due to social factors rather than natural decline, pointing out the limitations of existing population and social policies

Characteristics of Local Extinction Risk Areas

By looking at the areas where the three indices overlap in measuring local extinction, it is possible to find that risk areas are mainly distributed in rural areas. This can be inferred from the larger population of urban areas compared to rural areas, and it serves as an indicator that social mobility to cities is continuously active.

The urban population increased sharply until the early 1990s, and according to data from the Ministry of Land, Infrastructure and Transport and the Korea Land and Geospatial Informatix Corporation in 2022, the urban population ratio in Korea is about 92%, higher than the world average of 57%. In Korea, urban areas are classified based on administrative districts (dong/eup areas) and zoning areas (urban areas in zoning areas), and there is little difference between the urban populations calculated based on each standard.

Zoning area-based cities are widely distributed in metropolitan areas, where the urban population ratio is high. Looking at administrative districts, the proportion of myeon (rural areas) has decreased, while the proportion of dong/eup (urban areas) has increased. In particular, the composition ratio of dong/eup in the metropolitan area has continued to increase, reaching about 50% of the total in 2005, and is still higher than in other regions. As of 2024, the population concentration in the metropolitan area, where more than 50% of Korea’s total population lives, has intensified, and most of the population in that area lives in cities. This can also be found in the maps of urban population and urban area distribution by province and city/county/district in 2010 and 2020. The per capita urban area ratio is higher in areas with smaller populations than in large cities.

Even in areas that are not rural, the extinction risk area may develop into a social problem. Extinction risk is spreading extensively to large cities and old downtown areas with populations of more than 500,000. For example, despite being a metropolitan area, about 43.8% of Busan’s districts are at risk of extinction.

The increase in extinction risk areas can cause various social problems, such as increasing the burden of supporting older adults due to aging. Therefore, the government is making various policy responses and institutional efforts to improve social awareness.

Policy Responses to Local Extinction

Past policies to counter local extinction focused on ways to slow the population decline and improve the living conditions in extinction risk areas through economic and social means. However, the government’s current policy response has shifted to the establishment of a comprehensive response system considering various aspects of the problem.

The government’s policy response to local extinction risk areas focuses on improving policies to counter population decline, creating an environment where young people want to stay, enhancing the quality of life for residents in the areas, and implementing institutional policies for sustainable urban development. Specific policies include measures to support childcare and education, support for cultural and recreational activities, measures to revitalize the local economy through job creation, and policy support to create an environment where residents want to stay.

The regional extinction response model currently being considered is a mixed population model based on population composition, local economy, and social conditions. This model attempts to stabilize the population through various policy means, such as regional economic policies, local economic support, and local. development promotion, to create a population composition suitable for local circumstances. In addition, various models are being considered to address social problems related to local extinction, such as establishing living infrastructure and providing social services to improve the quality of life for residents.

In particular, it has been pointed out that policy efforts to improve public perception are also important. The government plans to promote a campaign to improve public awareness so that all citizens may be interested in and engage with the issue of local extinction, and plans to consider a policy response that emphasizes public participation.

In addition, academic efforts are being made to predict local extinction based on various data and to present new models to explain local extinction. Based on this, government institutions, academia, and research institutions are proposing more scientific and reasonable policy measures and response strategies and are actively working to prevent the acceleration of local extinction.

|

National Geography Information Institute (NGII) Copyright, |

|

Ministry of Land Infrastructure and Transport 국토교통부 국토지리정보원 |

|---|

.png)